By Francesca Smith, physics communications intern

Students who signed up for a course about the physics of sports probably did not expect to take a field trip to the Kohler Art Library at the beginning of the semester. But the unexpected is the norm with Jim Reardon, the instructor for Physics 106: Physics of Sports. While many science courses on campus consist largely of memorizing equations and staying ahead of the class curve, Reardon takes a multifaceted, participatory approach to teaching his students.

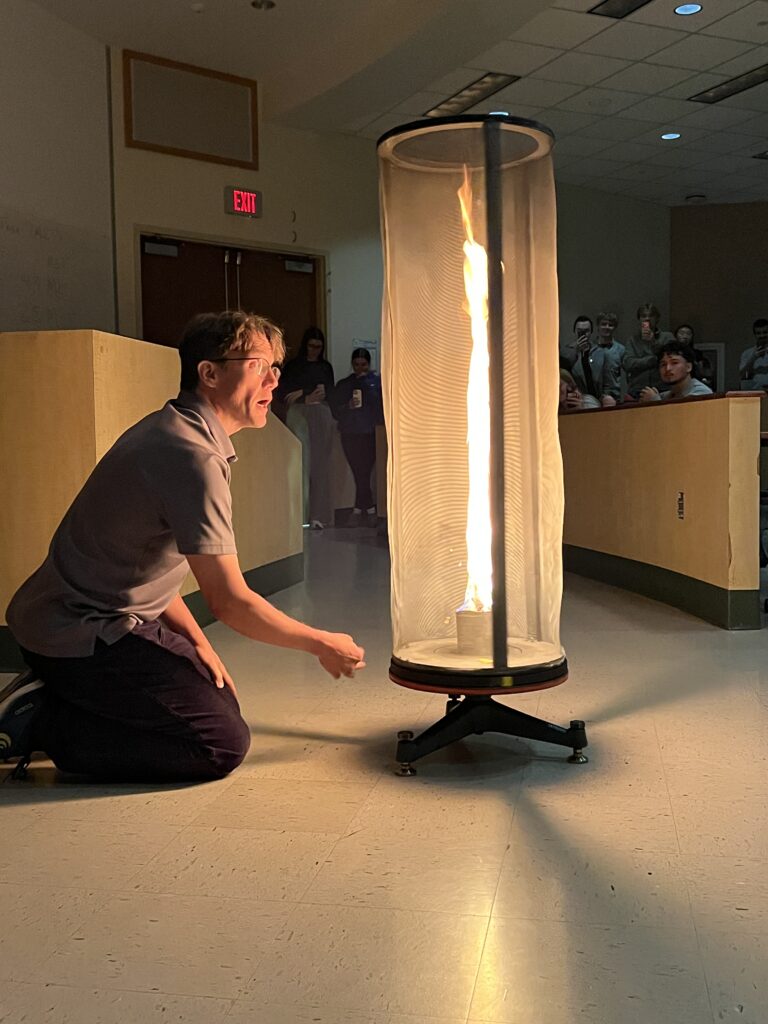

“You’re trying to put on a show that grabs their attention and effortlessly keeps it because you’re presenting a spectacle, like a movie,” Reardon says. “You don’t have to force yourself to pay attention to something that’s inherently interesting, it just sort of naturally goes there.”

At the library, Reardon has students flip through a first-edition copy of Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion from 1887, which shows phases of movement through photo sequences. Motion — so fundamental a concept to physics that Isaac Newton developed a set of laws around it — is commonly taught using a quantitative approach. Reardon uses Muybridge’s images to illustrate the concept of motion in a more intuitive way.

Reardon first developed Physics 106 with the help of fellow UW–Madison physics professor Cary Forest. The two were inspired by a similar course taught by one of Forest’s colleagues at UC Irvine, which was a favorite among students there. Physics of Sports was first taught at UW–Madison in Spring 2023, and initially resulted in 36 student enrollments. Now, three years later, course registration numbers have skyrocketed to approximately 300 undergraduates.

While the course’s theme attracts sports fans, Reardon’s unique methods of teaching also resonate with students, especially those intimidated by the idea of taking a college-level physics course. He follows a hands-on approach to teaching, where students are encouraged to, for example, run and jump in front of the classroom to demonstrate momentum. Field trips such as the aforementioned visit to the Kohler Art Library are also common in the course. Reardon used to work with The Wonders of Physics — the physics department’s educational outreach program — and noticed how audiences responded better to participation compared to lectures alone.

The course model also emphasizes lots of extra credit opportunities, which offer students a chance to improve their grades through additional work. If a student performs poorly on an exam, for instance, they then have the option to redeem their grade on the exam by demonstrating mastery of concepts they missed. In that sense, Reardon also uses Physics 106 to broaden the traditional standards of technical education. He points out that it’s as if students, when they were young, were divided into black-and-white categories of “good” and “bad” at math, which affects the confidence and success of students later on.

“And then we, at the college level, have to deal with that,” Reardon says. “Many of them I think would be quite successful, if they only didn’t have these mental blocks left from earlier.”

By utilizing a topic — sports such as baseball, basketball, football and more — that students find engaging, he can use this initial interest to help teach them about fundamental physics concepts such as impulse and energy. In that sense, Reardon seems to be his own kind of coach for the students in Physics 106: Physics of Sports. He considers an individual student’s success a team win, through a joint effort on their end and his.

“If I’m engaged to teach these students physics, then they’re going to get taught physics,” Reardon says. “So it takes a lot of extra work for me, but I do feel that there are a lot of gains to be made, too.”

Top photo: Everyone is an expert in torque even if they don’t know it yet, says Jim Reardon. Reardon (right, with teaching specialist Mitch McNanna PhD’23), uses familiar concepts — like a seesaw that most students played on at some point in their childhood — to illustrate physics topics such as torque.