Early in her thesis research, Jimena González was waiting. A lot.

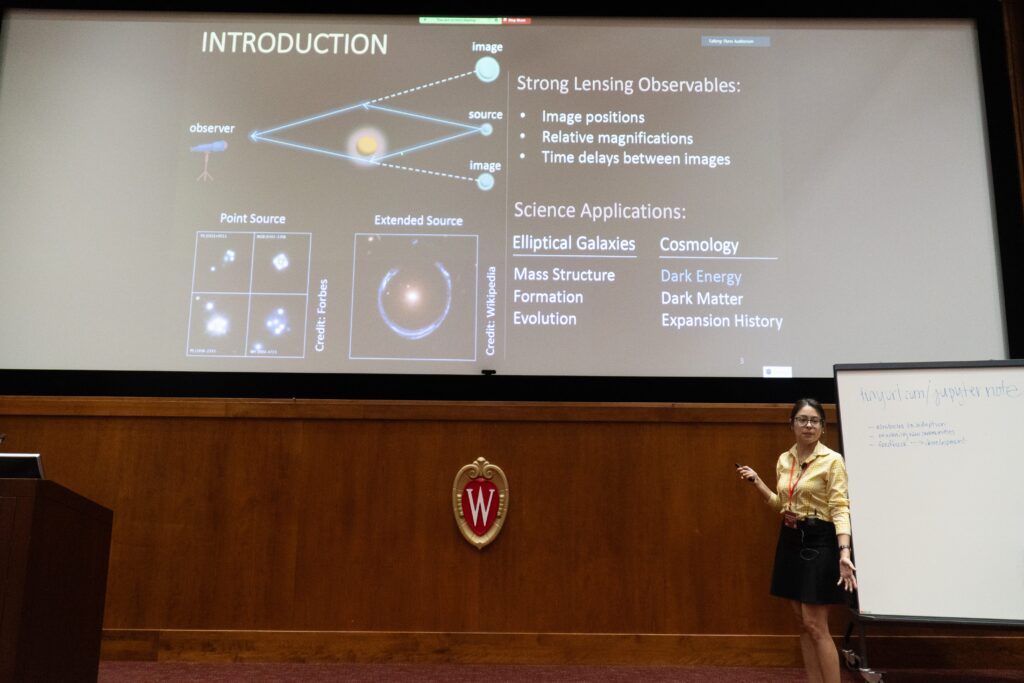

To better understand the nature of dark energy, she uses machine learning to search Dark Energy Survey cosmology data for evidence of strong gravitational lensing — where a heavy foreground galaxy bends the light of another galaxy, producing multiple images of it that can get so distorted that they appear as long arcs of light around the large galaxy in telescope images. She also focuses on finding very rare cases of strong gravitational lensing in which two galaxies are lensed by the same foreground galaxy, systems known as double-source-plane lenses.

First, she had to create simulations of the galaxy systems. Next, she used those simulations to train the machine learning model to identify the systems in the heaps and heaps of DES data. Lastly, she would apply the trained model to the real DES data. All told, she expected to find hundreds of “simple” strong gravitational lenses and only a few double-source-plane lenses out of 230 million images.

“But, for example, when I did the search the first time, I mostly only got spiral galaxies, so then I had to include spiral galaxies in my training,” says González, a physics graduate student in Keith Bechtol’s group.

The initial steps took around two weeks (hence the waiting) before she could even know what needed to be changed to better train the model. Once she had the model trained and would be ready to apply it to the entire dataset, she estimated it would take five to six years just to find the images of interest — and then she would finally be able to study the systems found.

Then, the email from the Open Science Grid (OSG) Consortium came. The OSG Consortium operates a fabric of distributed High Throughput Computing (dHTC) services, allowing users to take advantage of massive amounts of computing power. Researchers can apply to the OSG User School, an annual workshop for scientists who want to learn and use dHTC methods.

“[dHTC] is parallelizing things. It’s like if you had 500 exams to grade, you can distribute them among different people and it would take less time,” González says. “It sounded perfect for me.”

González applied and was accepted into the 2021 program, which was run virtually that year. At the OSG User School, she learned methods that would allow her to take advantage of dHTC and apply them to her work. Her multi-year processing time was cut down to mere days.

“Because it was so fast, there were many new things that I could implement in my research,” González says. “A lot of the methodology I implemented would not have been possible without OSG.”

This summer, González was selected as one of two recipients of the OSG David Swanson Award.

David Swanson was a longtime champion of and contributor to OSG, who passed away in 2016. In his memory, the award is bestowed annually upon one or more former students of the OSG User School who have subsequently achieved significant dHTC-enabled research outcomes.

She accepted the award at the Throughput Computing 2023 conference, where she presented her research and discussed how she used her training from the OSG User School to successfully comb through the DES data and find the systems of interest.

“When I got the award, I didn’t know anything about [Swanson],” González says. “But once I attended this event, I heard so many people talking about him, and I understood why it was created. It is such an honor to receive this award in his name.”