Physics professor Keith Bechtol and his research group have been key players in bringing the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile to the main stage. Now its state-of-the-art telescope has started taking its first images of the night sky.

Read the full article at: https://news.wisc.edu/uw-madison-physicists-play-key-role-in-international-observatory/Cosmology

UW–Madison physicists join Simons Observatory

In the 27 years that Peter Timbie has been a UW–Madison physics professor, he has largely been able to conduct cutting-edge research in the field of the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, with just himself and a handful of graduate students or other researchers in his group.

“You can’t do that anymore,” Timbie says. “Now, CMB experiments require hundreds of people. I finally decided that I’m not going to be able to do this on my own anymore.”

Timbie’s CMB colleague, assistant professor of physics Moritz Münchmeyer, joined the UW–Madison faculty in 2021 as a member of one of those large experiments: Simons Observatory. But his membership was a carryover from his time as a post-doc, and so he lost full access once he became an independent investigator.

“Simons Observatory is the big new CMB experiment that is upcoming, and it will push the field of CMB science forward,” Münchmeyer says. “For us to do state-of-the-art CMB science in the next five to ten years, and to set us up for the future, being in Simons Observatory is very important.”

In early 2024, Timbie and Münchmeyer were accepted as institutional members of Simons Observatory, granting them and their research groups full access to the collaboration of scientists and the wealth of data that Simons offers.

Simons Observatory is currently being built in the desert of the Chilean Andes and is expected to begin operations later this year. Its main goal is the detection of primordial gravitational waves — those from the Big Bang that have never been detected before.

“Primordial gravitational waves are expected to be produced by quantum mechanical effects in the early universe. This would be the first time that we observe direct evidence for quantum perturbations of space-time,” Münchmeyer says. “But it’s not known how large these waves are, so Simons Observatory could find them — which would be sensational news — otherwise, it will set tighter boundaries and exclude a lot of models.”

Münchmeyer, Timbie and their research groups would now be collaborators on this gravitational waves research, but they also have other interests in the CMB field that membership will help them address. CMB is radiation that comes from around 300,000 years after the Big Bang and is currently the earliest light in the universe that scientists can detect. CMB telescopes, including Simons, detect light in the microwave range and measure tiny temperature and polarization fluctuations at temperatures just a few degrees above absolute zero.

“CMB telescopes probe all the matter that this radiation encountered on its way from the Big Bang to us,” Münchmeyer says. “CMB light is scattering on charges in the universe, and then these interactions induce a change in temperature that we can measure.”

Münchmeyer and his group plan to use the new, more powerful Simons data to study two problems in CMB. First, the Simons data should be powerful enough to measure the kinetic Sunyaev–Zeldovich, or KSZ, effect, which he can use to measure the velocity field of the universe and probe properties of the primordial perturbations. Second, he plans to constrain models of inflation, which refers to the earliest times of the universe, before the so-called “hot” Big Bang.

“Inflation is where I started in cosmology ten years ago, and now Simons Observatory will have better data,” Münchmeyer says. “The interesting thing about inflation is that it happened at an energy scale that is far higher than the one a particle collider could probe, so it can probe the energy scales of grand unified theories or perhaps even quantum gravity, if a signal is found.”

Timbie, whose expertise lies in instrumentation and detector building, is looking forward to contributing to expansions of the Observatory that are already being planned. He also sees an opportunity for combining upcoming data from Simons with data from instruments he has helped design and build that study the universe closer to the present day.

“As Moritz mentioned, as the CMB travels to us from near the Big Bang, it’s distorted, but you can’t easily tell at what point during the excursion that those photons were disturbed,” Timbie says. “I’ve been working on a different experiment which is very good at mapping the universe in different slices heading back towards the Big Bang. And I think there’s a way to combine these datasets to add some information to the CMB data that would give us a very powerful tool for making large, three-dimensional maps of the Universe.”

Münchmeyer and Timbie certainly have the CMB expertise to have easily been accepted as Simons members, but membership also requires a fairly significant buy-in, which was fully supported by the UW–Madison department of physics, the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, and the College of Letters & Science. Their physics colleagues were instrumental in securing their membership.

“Our colleagues from accelerator physics, for example, were very supportive and pointed out that in the early days, before anyone was involved in the ATLAS or CMS experiments, the University had to buy into those collaborations,” Timbie says. “And of course, the payoff from that has been unbelievably large. The hope is maybe something similar will happen for us with the big CMB experiments.”

Of this potential, Münchmeyer adds: “After Simons Observatory, there will be the so-called CMB S4 experiment, which is the highest-ranked experiment in the new P5 Particle Physics report. The Department of Energy is very heavily investing in CMB physics.”

Simons Observatory’s Badger connections

Brian Keating, Timbie’s second graduate student, is the director of Simons Observatory; the Simons principal investigator, Mark Devlin ’88, worked with Prof. Dan McCammon as an undergraduate physics major

Earth-sized planet discovered in ‘our solar backyard’

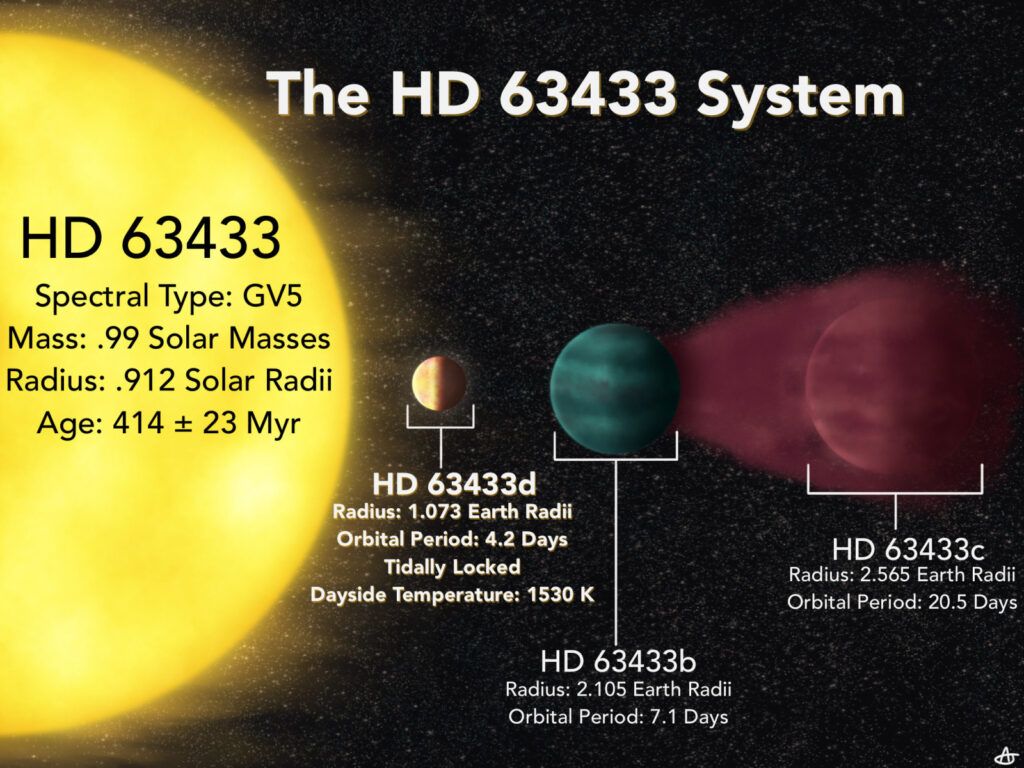

A team of astronomers have discovered a planet closer and younger than any other Earth-sized world yet identified. It’s a remarkably hot world whose proximity to our own planet and to a star like our sun mark it as a unique opportunity to study how planets evolve.

The new planet was described in a new study published this week by The Astronomical Journal. Melinda Soares-Furtado, a NASA Hubble Fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who will begin work as an astronomy and physics professor at the university in the fall, and recent UW–Madison graduate Benjamin Capistrant, now a graduate student at the University of Florida, co-led the study with co-authors from around the world.

“It’s a useful planet because it may be like an early Earth,” says Soares-Furtado.

UW physicists part of study offering unique insights into the expansion of the universe

This post is modified from one originally published by Fermilab

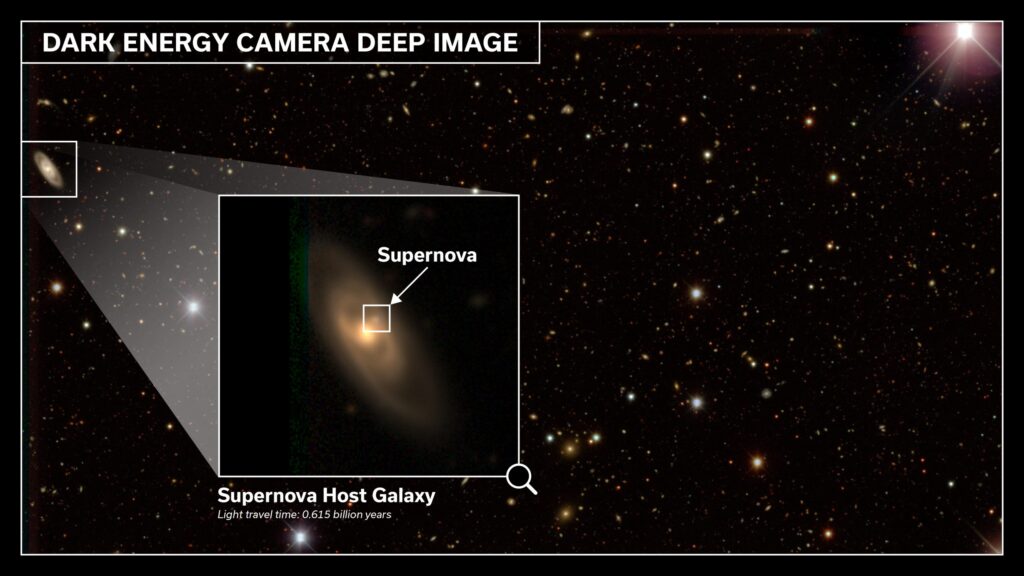

In the culmination of a decade’s worth of effort, the Dark Energy Survey collaboration of scientists analyzed an unprecedented sample of nearly 1,500 supernovae classified using machine learning. They placed the strongest constraints on the expansion of the universe ever obtained with the DES supernova survey. While consistent with the current standard cosmological model, the results do not rule out a more complex theory that the density of dark energy in the universe could have varied over time.

DES scientists presented the results January 8 at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society and have submitted them for publication to the Astrophysical Journal.

The work is the output of over 400 DES scientists, including UW–Madison physics professor Keith Bechtol and former graduate student Robert Morgan, PhD ’22.

In 1998, astrophysicists discovered that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate, attributed to a mysterious entity called dark energy that makes up about 70% of our universe. While foreshadowed by earlier measurements, the discovery was somewhat of a surprise; at the time, astrophysicists agreed that the universe’s expansion should be slowing down because of gravity.

This revolutionary discovery, which astrophysicists achieved with observations of specific kinds of exploding stars, called type Ia (read “type one-A”) supernovae, was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011.

In this new study, DES scientists performed analyses with four different techniques, including the supernova technique used in 1998, to understand the nature of dark energy and to measure the expansion rate of the universe.

As a graduate student in Bechtol’s group, Morgan was part of the DES supernova working group that worked to identify type Ia supernova. This group had to address two main concerns with the data to enhance detection fidelity.

“One is that there is some leakage of other types of supernovae into the sample, so you have to calibrate the rate of misclassification,” Bechtol explains. “Also, the brightness of the supernova gives us a way of estimating its distance, but there is a distribution of how bright the Ia supernovae are. Because we are slightly less likely to detect the intrinsically fainter supernovae, there is a small bias that needs to be accounted for.”

Bechtol has been part of the DES collaboration since its formation in 2012, serving as a co-convener of the DES’s Science Release Working Group for four years and a co-convener of the Milky Way Working Group for two years. His role in this new study was in data processing and presentation.

“We collect all of the data, process it, and then release it as a coherent set of data products, both for use by the DES collaboration and as part of public releases to the community,” Bechtol says. “One of the aspects I worked on is the photometric calibration — our ability to measure the fluxes of objects accurately and precisely. It’s an important part of the supernova analysis and something that I’ve been working on continuously over the past ten years.”

For the full story, please see the Fermilab news release

Physics PhD student Stephen McKay named ALMA ambassador

Congrats to physics graduate student Stephen McKay on being named an ALMA ambassador!

ALMA, or the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, is the largest radio telescope in the world. It can detect light radiated by clouds of dust grains in some of the earliest and most distant galaxies in the Universe. Researchers can submit proposals to ALMA that direct data collection to observe astronomical targets at a wide range of wavelengths, in order to accomplish many cutting-edge science goals. However, ALMA receives many more proposals than there is time to operate the telescope.

That’s where McKay’s ambassadorship comes in.

“Lots of groups at UW–Madison and other places will propose to get data from these telescope arrays,” McKay says. “In February, I’ll attend a training (through the ambassador program) where they will teach me tips and tricks for writing proposals. Then in early spring, I’ll run a proposal workshop here for anyone who wants to learn how to strengthen a proposal.”

McKay is no stranger to proposing and using ALMA data. A third-year graduate student in astronomy professor Amy Barger’s research group, he expects nearly all his publications will be based on ALMA data. His research focuses on old, distant galaxies and measuring and inferring physical properties about them: How massive are they? What is their rate of star formation? What processes trigger the rapid star-formation in these systems?

“The galaxies that I mainly study are faint or hard to detect in optical wavelengths or even near-infrared wavelengths. Until about maybe 25 years ago, we didn’t know a lot of these galaxies existed because they just weren’t visible in the typical telescope images we had,” McKay says. “The portion of the observed electromagnetic spectrum where these galaxies are brightest ranges from 500 microns to nearly one millimeter, which overlaps heavily with ALMA’s spectral coverage.”

Two years ago, McKay attended an ALMA workshop to learn more about how ALMA and similar radio arrays operate. With this ALMA ambassadorship, he will now help run the workshops and offer advice on crafting stronger proposals. The ALMA Ambassador Program is run through the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s North American ALMA Science Center (NAASC). It provides training and an up to $10,000 research grant to early-career researchers interested in expanding their ALMA/interferometry expertise and sharing that knowledge with their home institutions.

“This program is helpful for me because I will learn more in terms of how to actually do my own research, but then I can also pass along what I learn with the rest of the astronomical community,” McKay says.

Jimena González joins Bouchet Graduate Honor Society

This story was originally posted by the Graduate School

Five outstanding scholars, including Physics PhD student Jimena González, are joining the UW–Madison chapter of the national Edward Alexander Bouchet Graduate Honor Society this academic year.

The Bouchet Society commemorates the first person of African heritage to earn a PhD in the United States. Edward A. Bouchet earned a PhD in Physics from Yale University in 1876. Since then, the Bouchet Society has continued to uphold Dr. Bouchet’s legacy.

“The 2024 Bouchet inductees are making key contributions in their disciplines, as well as to the research, education, and outreach missions of our campus. They truly embody the Wisconsin Idea and are exemplary in every way,” said Abbey Thompson, assistant dean for diversity, inclusion, and funding in the Graduate School.

The Bouchet Society serves as a network for scholars that uphold the same personal and academic excellence that Dr. Bouchet demonstrated. Inductees to the UW–Madison Chapter of the Bouchet Society also join a national network with 20 chapters across the U.S. and are invited to present their work at the Bouchet Annual Conference at Yale University, where the scholars further create connections and community within the national Bouchet Society.

The UW–Madison Division of Diversity, Equity, and Educational Achievement supports each inductee with a professional development grant.

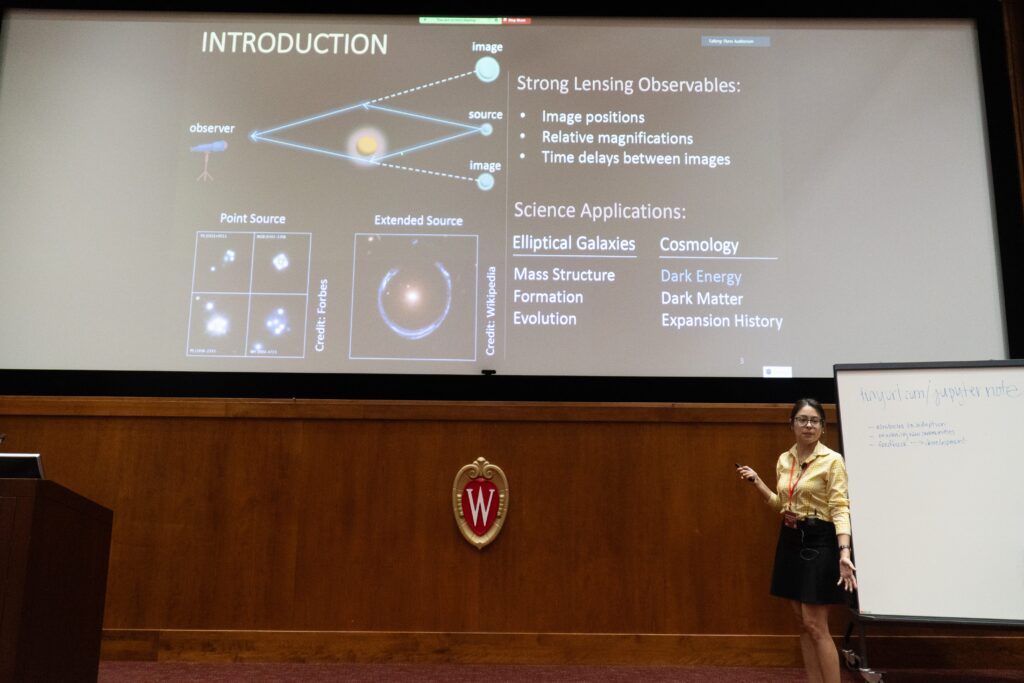

González is a physics PhD candidate specializing in observational cosmology. Her research centers on searching and characterizing strong gravitational lenses in the Dark Energy Survey. These rare astronomical systems can appear as long curved arcs of light surrounding a galaxy. Strong gravitational lenses offer a unique probe for studying dark energy, the driving force behind the universe’s accelerating expansion and, consequently, a pivotal factor in determining its ultimate fate.

During her graduate program, Jimena has received the Albert R. Erwin, Jr. & Casey Durandet Award and the Firminhac Fellowship from the Department of Physics. Additionally, she was honored with the 2023 Open Science Grid David Swanson Award for her outstanding implementation of High-Throughput Computing to advance her research. Jimena has contributed as a co-author to multiple publications within the field of strong gravitational lensing and has presented her work at various conferences. In addition to her academic achievements, Jimena has actively engaged in outreach programs. Notably, she was selected as a finalist at the 2021 UW–Madison Three Minute Thesis Competition and secured a winning entry in the 2023 Cool Science Image Contest. Her commitment to science communication extends to a contribution in a Cosmology chapter in the book AI for Physics. Jimena has also led a citizen science project that invites individuals from all around the world to inspect astronomical images to identify strong gravitational lenses. Jimena obtained her bachelor’s degree in physics at the Universidad de los Andes, where she was awarded the “Quiero Estudiar” scholarship.

Federal physics advisory panel — including Profs. Bose and Cranmer — announces particle physics recommendations

Earlier this year, physics professors Tulika Bose and Kyle Cranmer were selected to serve on the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel, or P5, a group of High Energy Physics experts that advises the Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Science Foundation’s Division of Physics on high energy and particle physics matters.

P5 announced their recommendations in a draft report published Dec. 7 — and UW–Madison physicists are featured in many of the projects.

One recommendation is to move forward with a planned expansion of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, an international scientific collaboration operated by the UW–Madison at the South Pole. Other recommendations include support for a separate neutrino experiment based in Illinois (the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, or DUNE); continuing investment in the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland and the Rubin Observatory in Chile; and expanding involvement in the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), a ground-based very-high-energy gamma ray observatory. UW–Madison physicists have leading roles in all of these research efforts.

Additional recommendations include the development of a next generation of ground-based telescopes to observe the cosmic microwave background and a direct dark matter detector experiment, among others.

Jimena González wins 2023 OSG David Swanson Award

Early in her thesis research, Jimena González was waiting. A lot.

To better understand the nature of dark energy, she uses machine learning to search Dark Energy Survey cosmology data for evidence of strong gravitational lensing — where a heavy foreground galaxy bends the light of another galaxy, producing multiple images of it that can get so distorted that they appear as long arcs of light around the large galaxy in telescope images. She also focuses on finding very rare cases of strong gravitational lensing in which two galaxies are lensed by the same foreground galaxy, systems known as double-source-plane lenses.

First, she had to create simulations of the galaxy systems. Next, she used those simulations to train the machine learning model to identify the systems in the heaps and heaps of DES data. Lastly, she would apply the trained model to the real DES data. All told, she expected to find hundreds of “simple” strong gravitational lenses and only a few double-source-plane lenses out of 230 million images.

“But, for example, when I did the search the first time, I mostly only got spiral galaxies, so then I had to include spiral galaxies in my training,” says González, a physics graduate student in Keith Bechtol’s group.

The initial steps took around two weeks (hence the waiting) before she could even know what needed to be changed to better train the model. Once she had the model trained and would be ready to apply it to the entire dataset, she estimated it would take five to six years just to find the images of interest — and then she would finally be able to study the systems found.

Then, the email from the Open Science Grid (OSG) Consortium came. The OSG Consortium operates a fabric of distributed High Throughput Computing (dHTC) services, allowing users to take advantage of massive amounts of computing power. Researchers can apply to the OSG User School, an annual workshop for scientists who want to learn and use dHTC methods.

“[dHTC] is parallelizing things. It’s like if you had 500 exams to grade, you can distribute them among different people and it would take less time,” González says. “It sounded perfect for me.”

González applied and was accepted into the 2021 program, which was run virtually that year. At the OSG User School, she learned methods that would allow her to take advantage of dHTC and apply them to her work. Her multi-year processing time was cut down to mere days.

“Because it was so fast, there were many new things that I could implement in my research,” González says. “A lot of the methodology I implemented would not have been possible without OSG.”

This summer, González was selected as one of two recipients of the OSG David Swanson Award.

David Swanson was a longtime champion of and contributor to OSG, who passed away in 2016. In his memory, the award is bestowed annually upon one or more former students of the OSG User School who have subsequently achieved significant dHTC-enabled research outcomes.

She accepted the award at the Throughput Computing 2023 conference, where she presented her research and discussed how she used her training from the OSG User School to successfully comb through the DES data and find the systems of interest.

“When I got the award, I didn’t know anything about [Swanson],” González says. “But once I attended this event, I heard so many people talking about him, and I understood why it was created. It is such an honor to receive this award in his name.”

Through machine learning maps, cosmic history comes into focus

By Jason Daley, UW–Madison College of Engineering

For millennia, humans have used optical telescopes, radio telescopes and space telescopes to get a better view of the heavens.

Today, however, one of the most powerful tools for understanding the cosmos is the computer chip: Cosmologists rely on processing power to analyze astronomical data and create detailed simulations of cosmic evolution, galaxy formation and other far-out phenomena. These powerful simulations are starting to answer fundamental questions of how the universe began, what it is made of and where it’s likely headed.

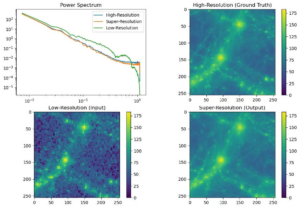

“It is extremely expensive to run these simulations and basically takes forever,” says Kangwook Lee, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “So they cannot run them for large-scale simulations or for high-resolution at that same time. There are a lot of issues coming from that.”

Instead, machine learning expert Lee and physics colleagues Moritz Münchmeyer and Gary Shiu are using emerging artificial intelligence techniques to speed up the process and get a clearer view of the cosmos.

Keith Bechtol, Victor Brar promoted to Associate Professors

Congratulations to Keith Bechtol and Victor Brar, who were both promoted to associate professors of physics with tenure!

Bechtol is an observational cosmologist with research interests in dark matter and dark energy, using the whole Universe as a lab to understand the fundamental physics of nature. He is part of the Dark Energy Survey (DES) that has cataloged more 500 million galaxies and thousands of supernovae to understand the nature of dark energy. He and his group are also working on the construction and commissioning of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in preparation for the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). LSST is expected to catalog more stars, more galaxies and more solar system objects during its first year of operations than all previous telescopes combined.

“Professor Bechtol plays a leading role in the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is now poised to enable a major leap in the data available for understanding the development of our universe,” says Mark Eriksson, Chair and John Bardeen Professor of Physics.

Bechtol was a co-convener of the DES’s Science Release Working Group for four years and a co-convener of the Milky Way Working Group for two years. He is now serving as Technical Coordinator for the LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration. In 2022, he was selected to the Department of Energy’s Early Career Research Program. He also proposed and is the faculty lead for the physics department’s Thaxton Fellowship, whose goal is to provide more equitable access to physics research experiences for undergraduates.

Brar, the Van Vleck professor of physics and a member of the Wisconsin Quantum Institute, is an experimental condensed matter physicist with a research focus on quantum materials and novel imaging techniques. His group works on developing metamaterials such as 2D materials for use in laser sailing or fabricating graphene structures for use in telecommunications. They also use scanning tunneling microscopy and scanning tunneling potentiometry to understand the physical and electrical properties of materials.

“The experiments performed by Professor Brar and his research team have enabled measurements of completely new regimes for electron transport in 2D materials,” Eriksson says.

Brar was awarded a Moore Inventor Fellowship in 2018, a Sloan Fellowship in 2021, and a National Science Foundation CAREER award in 2023. He has additionally received two UW–Madison Research Forward awards.