Quantum Computing

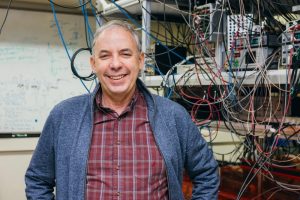

Mark Saffman wins Bell Prize

This post is derived from content originally published by the University of Toronto

Congrats to Mark Saffman, the Johannes Rydberg Professor of Physics and director of the Wisconsin Quantum Institute, on earning the ninth Biennial John Stewart Bell Prize for Research on Fundamental Issues in Quantum Mechanics and Their Applications.

He shares the prize with Antoine Browaeys (CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay) and Mikhail Lukin (Harvard) for their pioneering contributions to quantum simulation and quantum computing with neutral atoms in optical tweezer arrays, including the development of large-scale programmable arrays for scalable quantum computation. The prize will be given at the eleventh international conference on Quantum Information and Quantum Control, University of Toronto.

Saffman’s career-spanning work was also recognized last month with the American Physical Society’s Ramsey Prize in AMO Physics and in Precision Tests of Fundamental Laws and Symmetries, a prize he shares with Browaeys.

The John Stewart Bell Prize for Research on Fundamental Issues in Quantum Mechanics and their Applications (short form: “Bell Prize”) was established in 2009, and is awarded every other year, for significant contributions first published in the preceding 6 years. The award is meant to recognize major advances relating to the foundations of quantum mechanics and to the applications of these principles – this covers, but is not limited to, quantum information theory, quantum computation, quantum foundations, quantum cryptography, and quantum control. The award is not intended as a “lifetime achievement” award, but rather to highlight the continuing rapid pace of research in these areas, and the fruitful interplay of fundamental research and potential applications. It is intended to cover even-handedly both of these aspects, and to include both theoretical and experimental contributions.

2025 Nobel Prize Laureate John Martinis’s Connections to UW–Madison

Welcome, Prof. Josiah Sinclair!

When he was younger, UW–Madison assistant professor of physics Josiah Sinclair wanted to be a scientist-inventor when he grew up. In high school, he would ask questions in biology and chemistry classes that his teachers said were really physics questions. So, when he began his undergrad at Calvin University, he majored in physics, believing that experimental physics would be at the intersection of his interests. In the end, it was quantum physics that really fascinated him, motivating him to complete a PhD in experimental quantum optics and atomic physics at the University of Toronto. He says, “The ethos of my PhD group was this idea that with modern technology, maybe we can invent an apparatus that can reproduce the essential elements of this or that classic thought experiment and learn something new.” After completing a postdoc at MIT, Sinclair joined the UW–Madison physics department as an assistant professor in August, where he will tinker in the lab as an experimental quantum physicist, and just maybe invent a new kind of neutral atom quantum computer.

Please give an overview of your research.

There’s a global race underway to build a quantum computer—a machine that operates according to the laws of quantum mechanics and uses an entirely different, more powerful kind of logic to solve certain problems exponentially faster than any classical computer can. Quantum computers won’t solve all problems, but there’s strong confidence they’ll solve some very important ones. Moreover, as we build them, we’re likely to discover new applications we can’t yet imagine.

The approach my group focuses on uses arrays of single neutral atoms as qubits. Right now, the central challenge in practical quantum computing is how to scale up quantum processors without compromising their quality. Today’s atom-array quantum computers are remarkable, hand-built systems that have reached hundreds or even thousands of qubits in recent years—a truly impressive feat and possible in part due to pioneering work done right here in Madison. However, as these systems grow larger, we’re hitting fundamental size limits that call for new strategies.

My lab is working to develop modular interconnects for neutral-atom quantum computers. Instead of trying to build a single massive machine, we aim to link multiple smaller systems together using single photons traveling through optical fibers. The challenge is that single photons are easily misplaced, so to make this work, we need to develop the most efficient atom–photon interfaces ever built—pushing the limits of our ability to control the interaction between one atom and one photon.

Once we get these quantum links working, we’ll have realized the essential building block for a truly scalable quantum computer and maybe someday the quantum internet. Beyond computing, these technologies could also enable new kinds of distributed quantum sensors, where multiple quantum systems work together to detect extremely faint signals spread across a large area, like photons arriving from distant planets.

What are the one or two main projects your new group will work on?

Our main focus will be to build two neutral atom quantum processors in adjacent rooms and link them together with an optical fiber. This project will teach us how to integrate highly efficient photonic interfaces—such as optical cavities—with atom arrays, and how to precisely control the interactions between atoms and photons. Step by step, we aim to demonstrate atom-photon entanglement and eventually send quantum information back and forth through the fiber.

We’re collaborating with a new company called CavilinQ, a Harvard spin-out supported by Argonne National Lab, to integrate a new cavity design with the geometry we want to explore for atom-photon coupling. Because we intend to iterate rapidly on the cavity design, our setup will be built on a precision translation stage, allowing us to easily slide the system in and out and swap out cavity components.

Another project in the lab will focus on developing a new kind of cold-atom quantum sensor. Most current sensors rely on magneto-optical traps, which require bulky electromagnets and impose constraints that limit performance. We plan to explore magnetic-field-free trapping techniques that could lead to simpler, more compact, and ultimately higher-performance quantum sensors.

What attracted you to Madison and the university?

Well, for me professionally, Madison’s a powerhouse in atomic physics and quantum computing. There are groups here that have been highly influential since the beginning in developing neutral atoms as a platform for quantum information science. So there’s a strong atomic physics community here that has incredible overlap with my research interests, and a thriving broader quantum information community as well. Some people work best in isolation, but that is not who I am, so the prospects of joining this vibrant collaborative environment was very appealing to me.

I also really enjoyed all my interactions with the members of the search committee and other faculty here both during my interview and subsequent visits. On the personal side, my wife’s family is all in the Chicago area, so the prospects of being so close to one side of the family were very appealing. We have a 18-month-old daughter, and when we visited, we just had such a positive impression of Madison as a place to have a family and to grow up.

What is your favorite element and/or elementary particle?

It’s rubidium. I worked with it in my PhD, I worked with it in my postdoc, and I will work with it again. It’s simple. It has one electron in the outer valence shell, which makes it easy to work with. It was one of the first atoms to be laser cooled and one of the first to be Bose condensed, but I think it still has some tricks for us up its sleeve. I believe the first quantum computers are going to be built out of rubidium atoms. Some people (and companies) think we will need a more complicated atom, like strontium or ytterbium, but I think we already have the atom we need—we just need to figure out how to make it work.

What hobbies and interests do you have?

In the last year: spending time with my eighteen-month-old daughter. It’s been a special time. I also enjoy photography. I do some photography of research labs, but mostly I do adventure photography. I don’t think of myself as a particularly talented photographer, my specialty is more being willing to lug a heavy camera up a mountain. I also really enjoy cycling, rock climbing, reading, and traveling.

UW fostering closer research ties with federal defense, cybersecurity agencies

UW–Madison leaders seek to expand partnership with federal agencies to boost dual-use research funding.

Read the full article at: https://news.wisc.edu/uw-fostering-closer-research-ties-with-federal-defense-cybersecurity-agencies/Exploring Decades of Semiconductor Collaboration between Argonne National Lab & UW–Madison

UW–Madison and Argonne National Laboratory have built a portfolio of shared research for decades. Read how semiconductor researchers from all interest areas have benefited from this affiliation.

Read the full article at: https://chips.wisc.edu/2025/10/10/anl-partnership/New trapped-atom qubit technology translates to industry-ready quantum computing product

Matt Otten earns Air Force Young Investigator Research Program award

Matt Otten has won an Air Force Young Investigator Research Program (YIP) award, offered through the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

The program intends to support early-career scientists and engineers who show exceptional ability and promise for conducting basic research. Nearly 40 awards were expected to be made in this cycle.

The three-year, $450,000 award will fund a postdoctoral fellow in Otten’s group, who will work on quantum characterization, verification, and validation (QCVV) of quantum computers. QCVV asks if a quantum computer is working and what the device’s limitations are, in an effort to engineer a better system in future iterations.

With any quantum computer, researchers input different tasks and calculations under different conditions, then receive back some classical data that describes the quantum state. Otten describes what happens between input and output as “a black box.”

“Our work is trying to open that black box and put in physics,” Otten says. “And we’re starting from a good place: we already have good models of what those qubits do and how they’re supposed to behave, and we can fit the parameters of the model to the observations of the data.”

Otten’s group will collaborate with experimentalists on their quantum computers. If the data fit the model, it suggests that the quantum computer is behaving as predicted and that the researchers understand the full process. But if the data do not — and given that a major impediment to quantum computing has been understanding and controlling errors, this scenario is more likely — then the researchers will need to determine why.

“That’s the goal of the research, to develop the techniques so that we can tie the errors that we see in the data to a physical source for that error, and then we can give feedback to the experimentalists,” Otten says. “And maybe they can tell me what went wrong without doing this complicated QCVV, but as we build bigger and bigger systems, this problem becomes harder to solve.”

Qolab, the first UW–Madison-incubated quantum startup, joins the Chicago Quantum Exchange

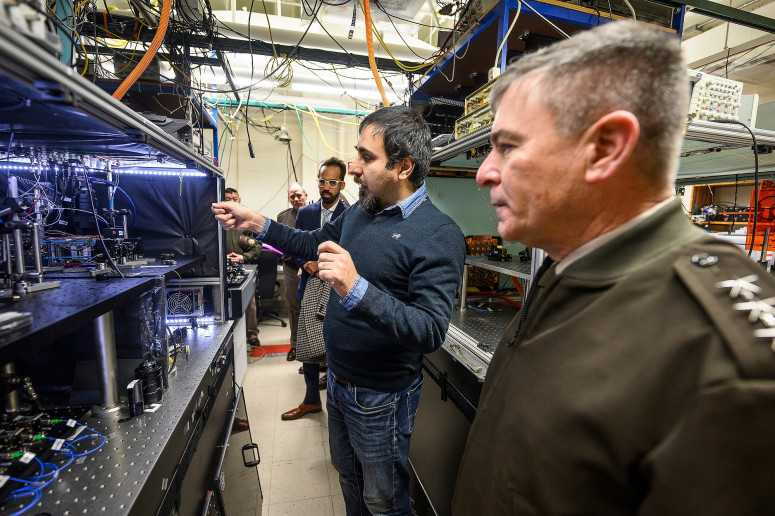

U.S. Cyber Command visit highlights UW–Madison’s leadership in cyber research and education

UW–Madison plays a leading role as a research and education partner for national cybersecurity. It reinforced this commitment recently by welcoming to campus a delegation from the United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), which is responsible for the Department of Defense’s cyberspace capabilities.

Read the full article at: https://news.wisc.edu/u-s-cyber-command-visit-highlights-uw-madisons-leadership-in-cyber-research-and-education/ Read the full article at:

Read the full article at: