Optical atomic clocks are already the gold standard for precision timekeeping, keeping time so accurately that they would only lose one second every 14 billion years. Still, they could be made to be even more precise if they could be pushed past the current limits imposed on them by quantum mechanics.

With two new grants from the U.S. Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command’s Army Research Laboratory, UW–Madison physics professor Shimon Kolkowitz proposes to introduce quantum entanglement — where atoms interact with each other even when physically distant — to optical atomic clocks. The improved clocks would allow researchers to ask questions about fundamental physics, and they have applications in improving quantum computing and GPS.

Atomic clocks are so precise because they take advantage of the natural vibration frequencies of atoms, which are identical for all atoms of a particular element. These clocks operate at or near the standard quantum limit, a fundamental limit on performance imposed on clocks where the atoms are all independent of each other. The only way to push the clocks past that limit is to achieve entangled states, strange quantum states where the atoms are no longer independent and they become intertwined.

“That turns out to be hard for a number of reasons. Entanglement requires these atoms to interact with each other, but a good clock requires them not to interact with each other or anything else,” Kolkowitz says. “So, you need to engineer a situation where you can make the atoms interact strongly, but you can also switch those interactions off. And those are some of the same requirements that are necessary for quantum computing.”

“That turns out to be hard for a number of reasons. Entanglement requires these atoms to interact with each other, but a good clock requires them not to interact with each other or anything else,” Kolkowitz says. “So, you need to engineer a situation where you can make the atoms interact strongly, but you can also switch those interactions off. And those are some of the same requirements that are necessary for quantum computing.”

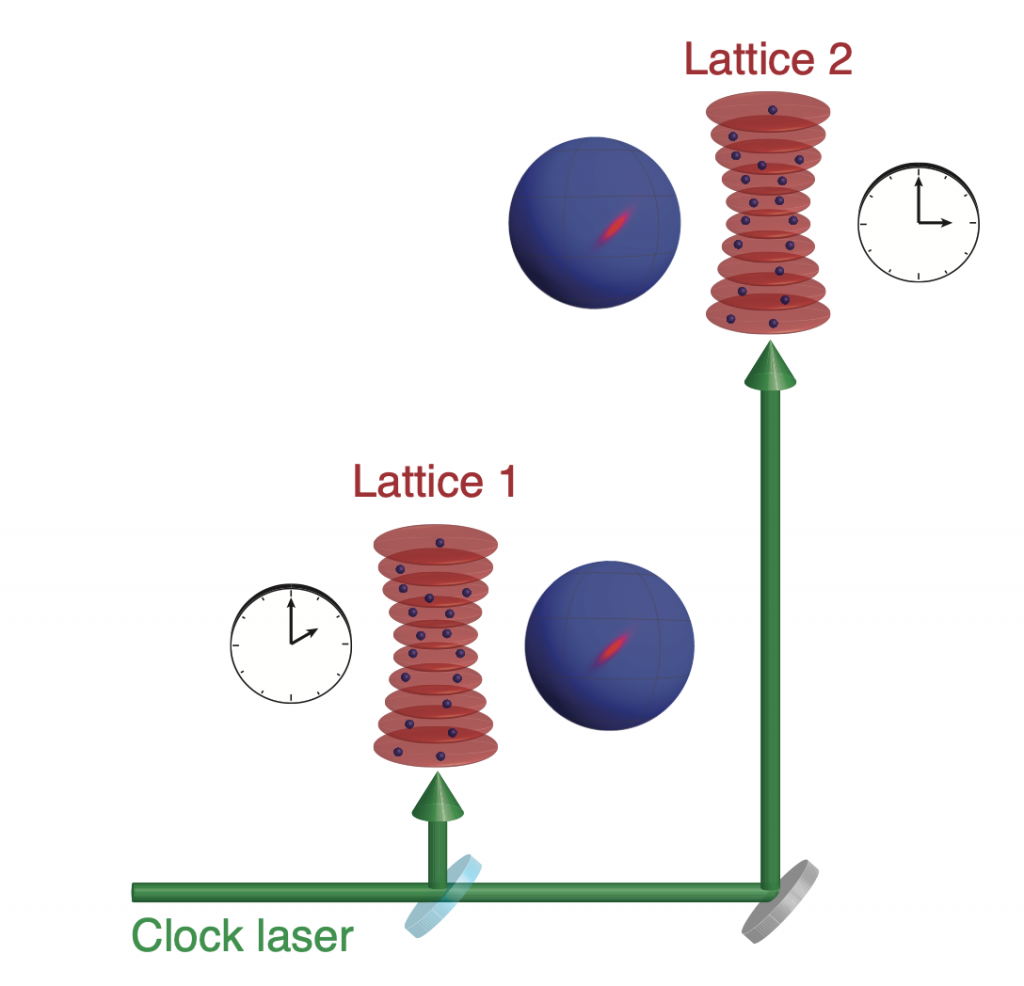

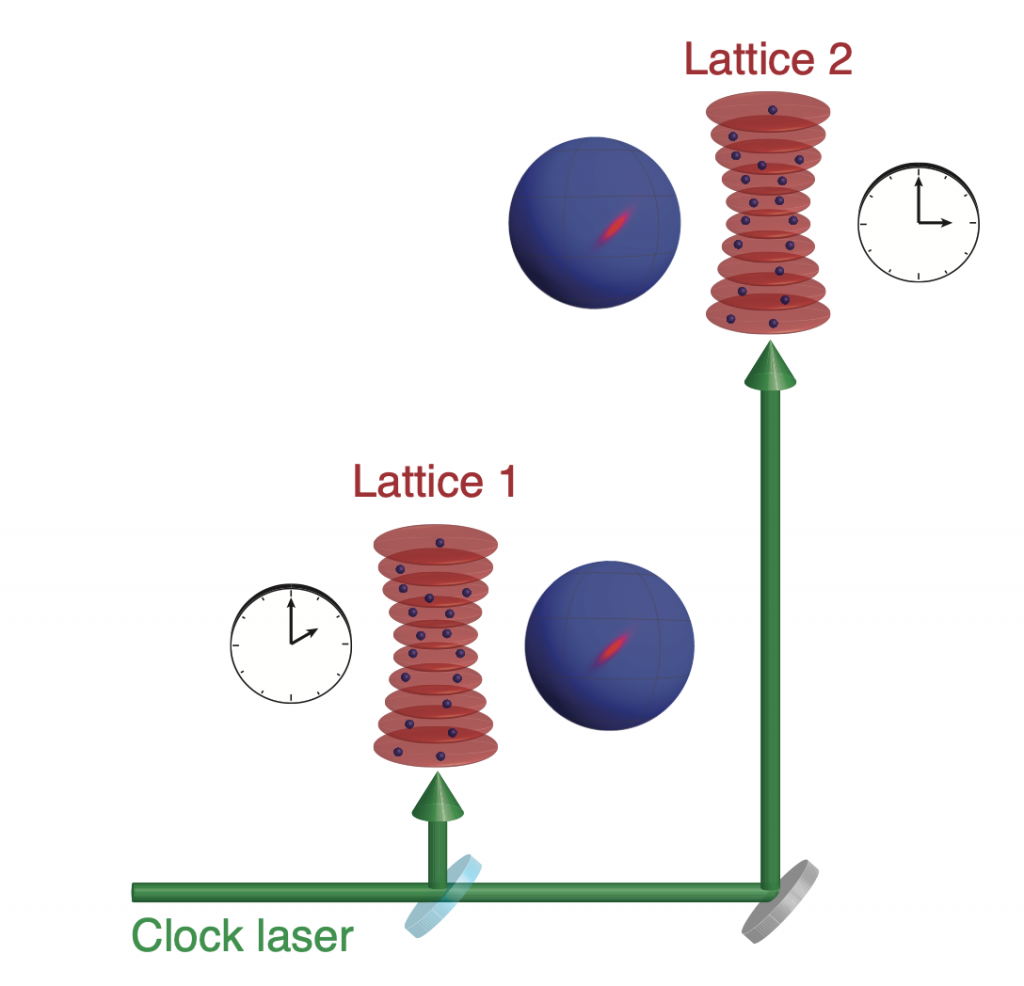

Kolkowitz is already building an optical atomic clock in his lab, albeit one that is not yet using entangled states. To make the clock, they first laser-cool strontium atoms to one millionth of one degree Celsius above absolute zero, then load the atoms into an optical lattice. In the lattice, the atoms are separated into what is effectively a tiny stack of pancakes — each atom can move around within their own flat disk, but they cannot jump into another pancake.

Though the atoms’ are stuck in their own pancake, they can interact with each other if their electrons are highly excited. This type of atom, known as Rydberg atoms, becomes close to one million times larger than an unexcited counterpart because the excited electron can be microns away from the nucleus.

“It’s kind of crazy that a single atom can be that big, and when you make them that much bigger, they interact much more strongly with each other than they do in their ground states,” Kolkowitz says. “Basically it means you can go from the atoms not interacting at all to interacting very strongly. That’s exactly what you want for quantum computing, and it’s what you want for this atomic clock.”

With the two ARO grants, Kolkowitz expects to generate Rydberg atoms in his lab’s atomic clock. One of the grants, a Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP), will fund the specialized UV laser that generates the high energy photons needed to excite the atoms into the highly excited Rydberg states. The second grant will fund personnel and other supplies. Kolkowitz will collaborate with UW–Madison physics professor Mark Saffman, who, along with physics professor Thad Walker, pioneered the use of Rydberg atoms for quantum computing.

In addition to being useful for developing new approaches to ask questions about fundamental physics in his research lab, these ultraprecise atomic clocks are of interest to the Department of Defense for atomic clock-based technologies such as GPS, and because they can be used to precisely map Earth’s gravity.