The National Science Foundation has selected a proposal “Compact and robust quantum atomic sensors for timekeeping and inertial sensing” by an interdisciplinary team led by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers for...

Read the full article at: https://engineering.wisc.edu/blog/choy-leads-team-awarded-national-science-foundation-quantum-sensing-challenge-grant/NSF

Physics researchers named part of $18M NSF materials research center

The Department of Physics is part of a six-year, $18 million grant awarded to the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) by the National Science Foundation. The award creates a National User Facility for X-FAST (XUV Femtosecond Absorption Spectroscopy Tabletop), a powerful XUV laser developed in the department.

MRSEC brings together 30 affiliated faculty from across nine departments to answer fundamental questions in materials science. The two interdisciplinary research groups (IRGs) funded by the award include one on stability in supercooled glasses and a second on magnetics in strained membranes. Physics professor Uwe Bergmann is a co-lead on IRG-2 along with materials science and engineering professor and physics affiliate faculty member Jason Kawasaki.

“The idea of our IRG is to make thin membranes of materials and then by straining them in various ways, changing their properties,” Bergmann says. “And our specific role is that we are in charge of x-ray and ultrafast characterization.”

The membranes being studied are 20-50 nanometer thin, crystalline materials. Kawasaki developed a way to produce very strong strains, up to 10%, which disrupt the perfect crystal lattice when applied. Once the atoms are pulled out of equilibrium by the strain, the energy levels change a little, the bonding changes, and exotic new phases are introduced. Bergmann is part of the IRG-2 team whose role is to perform ultrafast characterization of these changes. His team then informs the simulations group, whose theoretical calculations inform Kawasaki’s sample synthesis group.

“This is the typical circle between making the sample, finding out its properties, and understanding the properties — and then feeding it back to make new samples,” Bergmann says. “We’re trying to characterize these properties so that we can tailor them, so we can control them with light.”

Being able to control the materials’ properties with fast, electromagnetic light pulses could be a boon to faster, more efficient computing and telecommunications, an important potential application of this work.

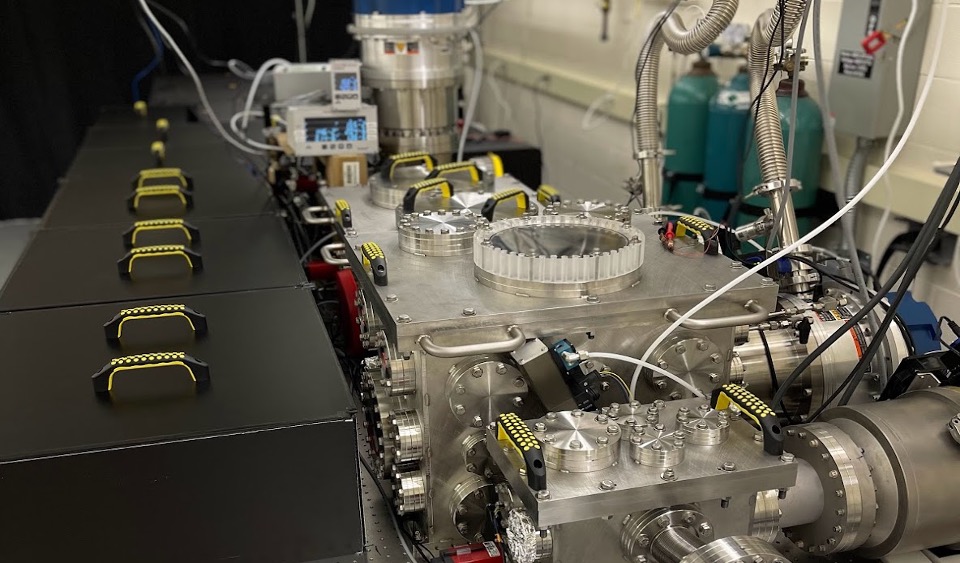

Bergmann’s role in MRSEC stems from his expertise in ultrafast x-ray spectroscopy. Since joining the department of physics in 2020, his group has developed and built the XUV transient absorption high harmonic generation instrument that will be used to characterize the changes in properties as a result of intense strain on the materials following ultrafast excitations. As part of the new funding, the X-FAST instrument is now a National User Facility, which provides access to researchers across the country. In addition, the new award is funding an upgrade that includes the terahertz (microwave to infrared) range for sample excitation, a range that team member and physics affiliate professor Jun Xiao has developed.

In addition to the two research thrusts, MRSEC also runs a robust outreach and education program as part of the funding.

MRSEC is one of 21 NSF-funded centers that conduct fundamental materials research, education and outreach at the nation’s leading research institutions. Paul Voyles, professor of materials science and engineering professor at UW–Madison, is MRSEC’s director.

Ke Fang earns NSF CAREER award

Congrats to Ke Fang, assistant professor of physics, WIPAC faculty member, and HAWC spokesperson, on earning an NSF CAREER award! CAREER awards are NSF’s most prestigious awards in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization.

Fang’s award is sponsored by the NSF Windows on the Universe: Multimessenger Astrophysics program. In multimessenger astrophysics, scientists search for multiple high energy signals to identify their sources and learn more about the makeup of our universe. WIPAC hosts both the IceCube neutrino telescope and the HAWC gamma ray telescope, and Fang says she is excited to have access to high-quality data from both. In her NSF proposal, she plans to use that data in two ways.

“One is evolving novel data analysis techniques to study the problems that remain outstanding, such as the source of high-energy neutrinos,” Fang says. “The second part is once we have these data analysis results, then we’ll use numerical simulations to understand our observations.”

In addition to an innovative research component, NSF proposals require that the research has broader societal impacts, such as working toward greater inclusion in STEM or increasing public understanding of science. Once again, Fang finds herself well-positioned at WIPAC, where the outreach team has developed Master Classes, a one-day event where high school students come to WIPAC, spend time with scientists, and learn about topics not typically covered in high school physics class. Currently, the students learn about IceCube’s instrumentation and how to analyze the complex detector data.

“The course is already well designed, but from my perspective, I use a lot of numerical simulation in my research, so one thing I proposed to do is that I would design a module that would incorporate some of these modern numerical study techniques into the master class,” Fang says. “The students will now learn how to study physics using supercomputers, using numerical simulations.”

Shimon Kolkowitz earns NSF CAREER award

Shimon Kolkowitz has already developed one of the most precise atomic clocks ever. Now, the UW–Madison physics professor has been awarded a Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to use his atomic clocks to potentially answer some big questions about the physics of our universe.

The five-year, $800,000 in total award will cover research expenses, graduate student support, and outreach projects based on the research.

“I am honored and proud to receive an NSF CAREER award, which will help my research group expand our experimental efforts and build upon our recent results,” Kolkowitz says. “This award will support research into new ways to harness the remarkable precision of optical atomic clocks for exciting physics applications such as searching for dark matter and detecting gravitational waves.”

Atomic clocks are so precise because they take advantage of the natural vibration frequencies of atoms, which are identical for all atoms of a particular element. Kolkowitz and his research group have developed atomic clocks that can detect the difference in these frequencies between two clocks that would only disagree with each other by one second after 300 billion years, the tiniest detectable frequency changes to date. These clocks, then, can measure effects that shifts their frequency by only 0.00000000000000001%, opening the possibility of using them in the search for new physics.

A significant advancement in Kolkowitz’s clocks is that they are multiplexed, with six or more separate clocks in one

vacuum chamber, effectively placing each clock in the same environment. Mutliplexing means that comparisons between the clocks, and not their individual accuracy, is what matters — and allows the group to use commercially available, robust and portable lasers in their measurements. Though the clocks are not yet ready to be used to detect gravitational waves, Kolkowitz says the current setup “looks a bit like how you would eventually do that,” and will allow him to test out and demonstrate the concept.

In the spirit of the Wisconsin Idea and the NSF’s “broader impacts” to benefit society beyond scientific merit, with this award, Kolkowitz will focus efforts on quantum science outreach with pre-college students.

“We’ll be developing new demos and hands-on activities designed to introduce K-12 students to modern physics concepts,” Kolkowitz says. “We’ll use these activities to engage students at live shows and interactive events as part of The Wonders of Physics outreach program, with an emphasis on reaching rural and Native American communities in Wisconsin.”

NSF established these awards to help scientists and engineers develop simultaneously their contributions to research and education early in their careers. CAREER funds are awarded by the federal agency to junior-level faculty at colleges and universities.

Balantekin named co-PI on NSF grant to solve cosmic mystery

This story has been modified from one originally published by New York Institute of Technology.

A team of University of Wisconsin–Madison and New York Institute of Technology physicists has secured a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) in an attempt to solve one of science’s greatest mysteries: how the universe formed from stardust.

Many of the universe’s elements, including the calcium found in human bones and iron in skyscrapers, originated from ancient stars. However, scientists have long sought to understand the cosmic processes that formed other elements—those with undetermined origins. Now, UW–Madison professor of physics Baha Balantekin and co-principal investigator Eve Armstrong assistant professor of physics at New York Institute of Technology, will perform the first known research project that uses weather prediction techniques to explain these events. Their revolutionary work will be funded by a two-year $299,998 NSF EAGER grant, an award that supports early-stage exploratory projects on untested but potentially transformative ideas that could be considered “high risk/high payoff.”

While the Big Bang created the first and lightest elements (hydrogen and helium), the next and heavier elements (up to iron on the periodic table) formed later inside ancient, massive stars. When these stars exploded, their matter catapulted into space, seeding that space with elements. Eventually, stardust matter from these supernovae formed the sun and planets, and over billions of years, Earth’s matter coalesced into the first life forms. However, the origins of elements heavier than iron, such as gold and copper, remain unknown. While they may have formed during a supernova explosion, current computational techniques render it difficult to comprehensively study the physics of these events. In addition, supernovae are rare, occurring about once every 50 years, and the only existing data is from the last explosion in 1987.

Large information-rich data sets are obtained from increasingly sophisticated experiments and observations on complicated nonlinear systems. The techniques of Statistical Data Assimilation (SDA) have been developed to handle very nonlinear systems with sparsely sampled data. SDA techniques, akin to the path integral methods commonly used in physics, are used in fields ranging from weather prediction to neurobiology. Armstrong and Balantekin will apply the SDA methods to the vast amount of data accumulated so far in neutrino physics and astrophysics.

With simulated data, in preparation for the next supernova event, the team will use data assimilation to predict whether the supernova environment could have given rise to some heavy elements. If successful, these “forecasts” may allow scientists to determine which elements formed from supernova stardust.

This project will provide an opportunity to the Physics graduate students interested in neutrinos to master an interdisciplinary technique with many other applications.

“Physicists have sought for years to understand how, in seconds, giant stars exploded and created the substances that led to our existence. A technique from another scientific field, meteorology, may help to explain an important piece of this puzzle that traditional tools render difficult to access,” says Armstrong.

The NSF is an independent agency of the U.S. government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National Institutes of Health. NSF funding accounts for approximately 27 percent of the total federal budget for basic research conducted at U.S. colleges and universities.

This project is funded by NSF EAGER Award ID No. 2139004.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF.