A month ago, the Seattle Community Summer Study Workshop—July 17-26, 2022, at the University of Washington—brought together over a thousand scientists in one of the final steps of the Particle Physics Community Planning Exercise. The meetings and accompanying white papers put the cherry on top of a period of collaborative work setting a vision for the future of particle physics in the U.S. and abroad. Later this year, the final report identifying research priorities in this field will be presented. Its main purpose is to advise the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation on research for their agendas during the next decade.

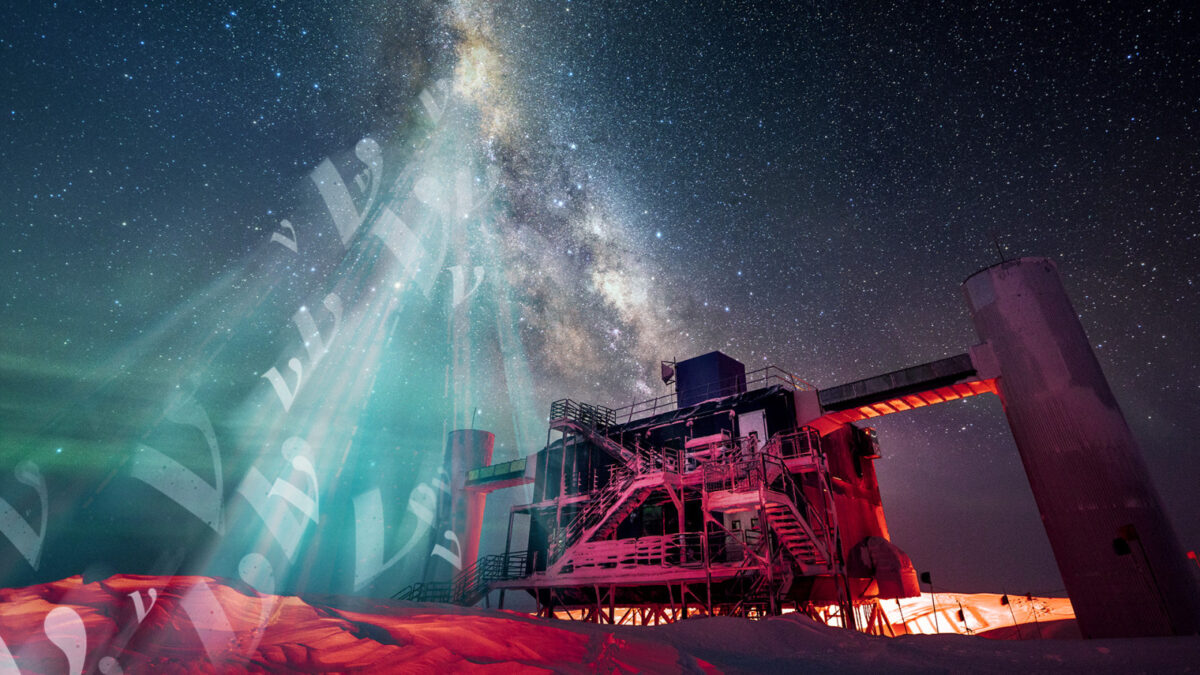

As new and old detectors once again prepare to expand the frontiers of knowledge, we asked some IceCube collaborators about the role the South Pole neutrino observatory should play in the bright future that lies ahead for particle physics.

Q: What type of neutrinos are currently detected in IceCube? And will that change with the future extensions?

The vast majority of the neutrinos we detect are generated in the atmosphere by cosmic rays, but we also have on the order of 1,000 cosmic neutrinos at energies above 10 TeV. We use the atmospheric neutrinos for a wide range of science, first of all to study the neutrinos themselves.

IceCube has detected more than a million neutrinos to date. That’s already a big number for neutrino scientists, and we will detect even more in the future. The deployment of the IceCube Upgrade, an extension of our facility targeting neutrinos at lower energies, will increase the density of sensors in IceCube’s inner subdetector, DeepCore, by a factor of 10. And a second, larger extension is also in the works. With IceCube-Gen2, we will improve the detection at the highest energies, too: the IceCube volume will increase by almost a factor of 10, and our event rate for high-energy cosmic neutrinos will also grow by an order of magnitude.

Albrecht Karle, IceCube associate director for science and instrumentation and a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

Q: Are the futures of IceCube and that of particle physics intrinsically linked?

Absolutely! Many open questions in particle physics have neutrinos at the center. What’s their mass? What is the behavior of neutrino flavor mixing? Are there right-handed (sterile) neutrinos? Neutrinos are particularly attractive in the search for new physics. We can answer all these questions, to varying levels, within IceCube and especially moving forward with the IceCube Upgrade and IceCube-Gen2.

Erin O’Sullivan, an associate professor of physics at Uppsala University

IceCube, the Icecube Upgrade, and IceCube-Gen2 can all uniquely contribute to the study of particle physics, in particular, neutrino physics, beyond Standard Model (BSM) physics, and indirect searches of dark matter. The IceCube Upgrade provides complementary and independent measurements of neutrino oscillation in addition to the long-baseline experiments. And IceCube-Gen2 will be crucial to exploring the BSM features, such as sterile neutrinos and secret neutrino interactions, at an energy that cannot be reached by the underground facilities. It will also be a discovery machine for heavy dark matter particles.

Ke Fang, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

Q: Talking about discoveries, now that both IceCube and Super-Kamiokande have reported definitive observations of tau neutrinos in atmospheric and astrophysical neutrino data, why should the international particle physics community continue to improve their detection?

The tau neutrino was discovered at Fermilab in an emulsion experiment where they observed double-bang events with a distance on the order of 1 mm separating production and decay. Since they represent the least studied neutrino and, in fact, one of the least studied particles, improved measurements of tau properties may reveal that the 3×3 matrix is not unitary and expose the first indication of physics beyond the 3-flavor oscillation scenario.

Francis Halzen, IceCube PI and a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

We are the only experiment operating currently (and in the foreseeable future) that is able to identify tau neutrinos on an event-by-event basis. We can do so by looking at the distinct morphological features they produce in our data at the highest energies. And with the IceCube Upgrade, we will also be the experiment that collects the most tau neutrinos. I suspect that these neutrinos will surprise us again and point us towards new physics.

Carlos Argüelles, an assistant professor of physics at Harvard University.

Four hundred years from now, people may see IceCube the way we see Galileo’s telescope, not as an end but as the beginning of a new branch of science. The astrophysical observation of tau neutrinos is but one piece in a large number of studies that IceCube can conduct, including the study of fundamental physics using astrophysical neutrinos.

Ignacio Taboada, IceCube spokesperson and a professor of physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology

Q: In 2019, the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center joined the Interactions Collaboration, which includes all major particle physics laboratories around the globe. The IceCube letter of introduction to this community detailed some of the most accurate results to date in neutrino physics. What’s unique about IceCube neutrino science?

One unique aspect of IceCube is the breadth of neutrino energy that we can measure, all the way down to the MeV energy scale in the case of a galactic supernova and up to as far as a few PeV neutrinos, which are the highest energy neutrinos ever detected. Therefore, IceCube provides us with different windows to study the neutrino and understand its properties. Especially in the context of searching for new physics, this is important as these processes can manifest at a particular energy scale but not be visible at other energy scales.

Erin O’Sullivan, an associate professor of physics at Uppsala University

Q: Let’s focus on high-energy neutrinos for a moment. What are the needs for their detection and why is the South Pole ice the perfect place for those searches?

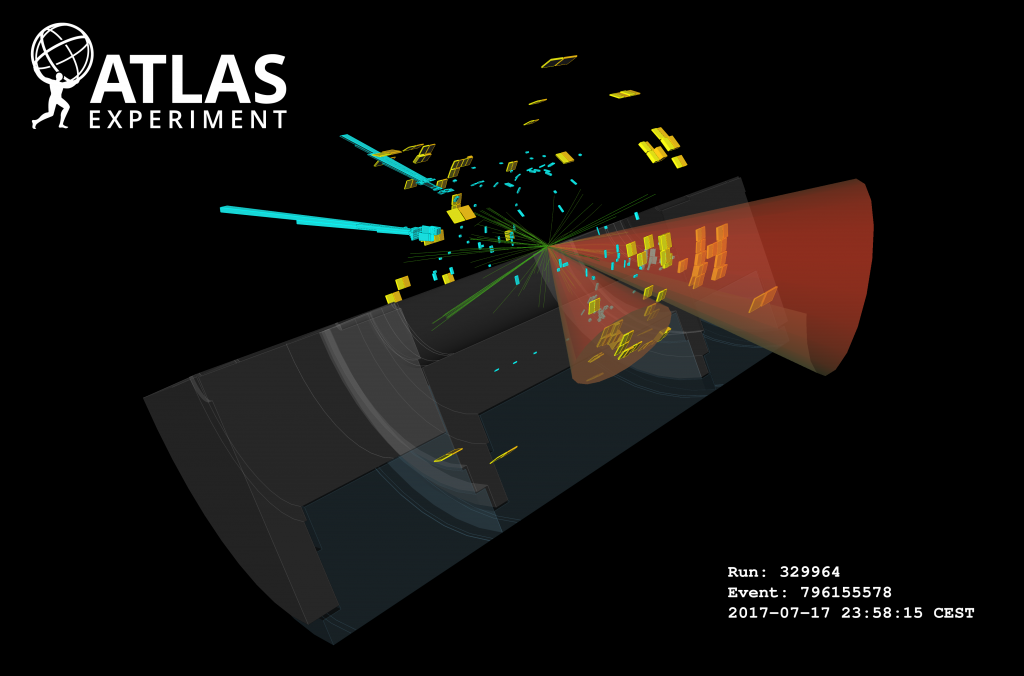

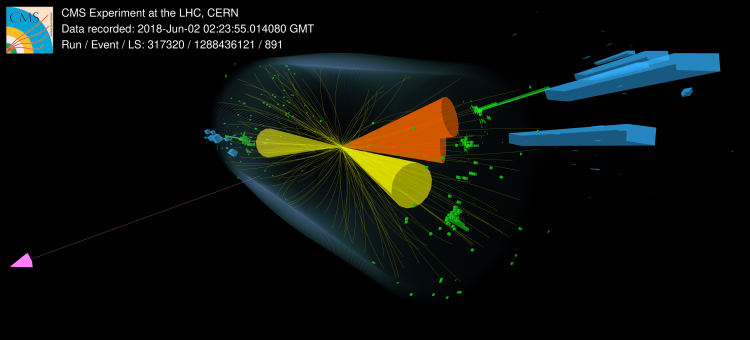

The highest energy neutrinos can be directly linked to the most powerful accelerators in the universe but also allow us to test the Standard Model at energies inaccessible to current or future planned colliders.

And why the South Pole? Well, what makes the South Pole such an optimal location are the exceptional optical and radio properties of its ice sheet, which is also the largest pool of ice on Earth. Neutrino event rates are very low at these energies and, thus, we need a huge detector to measure them.

Deep-ice Cherenkov optical sensors have already been proven as high-performing detectors for TeV and PeV neutrinos when deployed at depths of 1.4 km and greater below the surface. And radio technology is promising because radio waves can travel much further than optical photons in the ice, plus they work at shallow depths. So, when searching for the highest energy neutrinos using the South Pole ice sheet, radio neutrino detectors might be the only solution that scales up. Radio waves are able to travel further in the South Pole than in Greenland, for example. It’s a gift from nature to have this giant, pure block of ice to catch elusive neutrinos from the most powerful accelerators.

Lu Lu, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

Q: And what about the lowest energies? How does IceCube perform there?

IceCube’s DeepCore detector was especially designed for that: a more dense layout of photodetectors embedded in the center of IceCube and located at about 2 km depth, it uses the surrounding IceCube sensors to eliminate essentially all background from the otherwise dominant cosmic ray muons. This means that DeepCore can now be analyzed as if it was at 10 km depth, deeper than any mine on Earth. In the near future, the IceCube Upgrade will add seven strings of new sensors inside DeepCore, which will hugely increase its precision for neutrino properties.

Albrecht Karle, IceCube associate director for science and instrumentation and a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

IceCube’s low energies are what all other neutrino experiments would call high energies. This is a regime where the neutrino interactions are well predicted from accelerator experiments, which means that if deviations are found in the data we can claim new physics. Thus, IceCube and the upcoming IceCub Upgrade results are not only going to yield some of the most precise measurements on the neutrino oscillation parameters but also—and more importantly—test the neutrino oscillation framework.

Carlos Argüelles, an assistant professor of physics at Harvard University

Q: And, last but not least, we should think about the people that will make all this possible. What efforts are underway to diversify who does science and make the field more equitable?

Four years ago, IceCube invited a few collaborations to join efforts to increase equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) in multimessenger astrophysics. With support from NSF, this was the birth of the Multimessenger Diversity Network (MDN). This network now includes a dozen participating collaborations, which is an indication of the growing awareness and action to increase DEIA across the field. Set up as a community of practice, where people share their knowledge and experiences with each other, the MDN is a reproducible and scalable model for other fields. We are excited to see this community of practice grow, to contribute with resources and experiences, and to learn from others.

For the first time in an official capacity, DEIA efforts were included in the Snowmass planning process and were also incorporated into the Astro2020 Decadal Survey. One take-away from these processes is that more resources and accountability are needed to speed up DEIA efforts.

Ellen Bechtol, MDN community manager and an outreach specialist at the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center

Read more about IceCube and its future contributions to particle physics