By Alex Lazarian, Yue Hu, and Ka Wai Ho

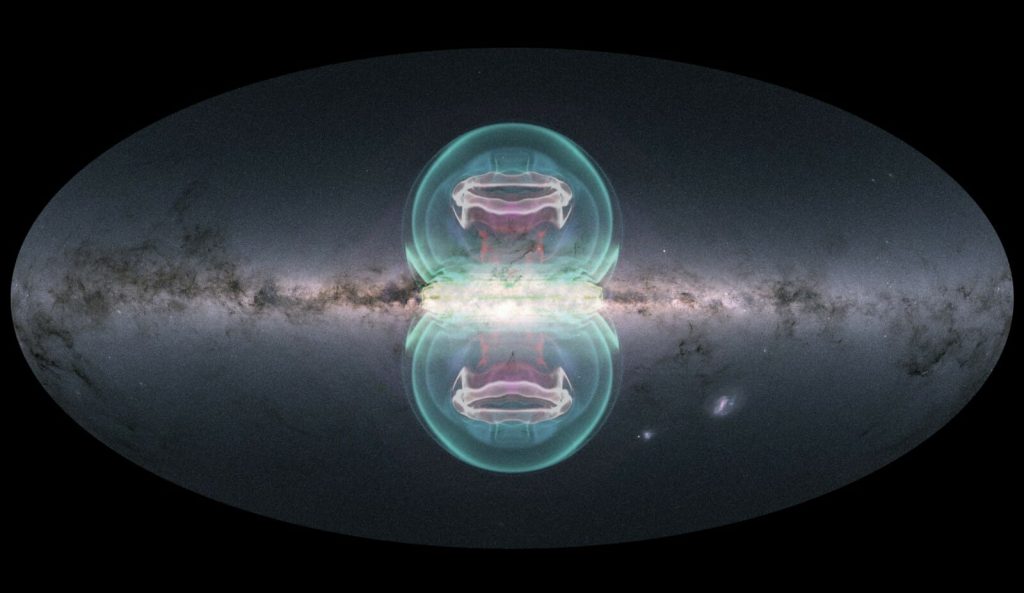

Galaxy clusters, immense assemblies of galaxies, gas, and elusive dark matter, form the cornerstone of our Universe’s grandest structure — the cosmic web. These clusters are not just gravitational anchors, but dynamic realms profoundly influenced by magnetism. The magnetic fields within these clusters are pivotal, shaping the evolution of these cosmic giants. They orchestrate the flow of matter and energy, directing accretion and thermal flows, and are vital in accelerating and confining high-energy charged particles/cosmic rays.

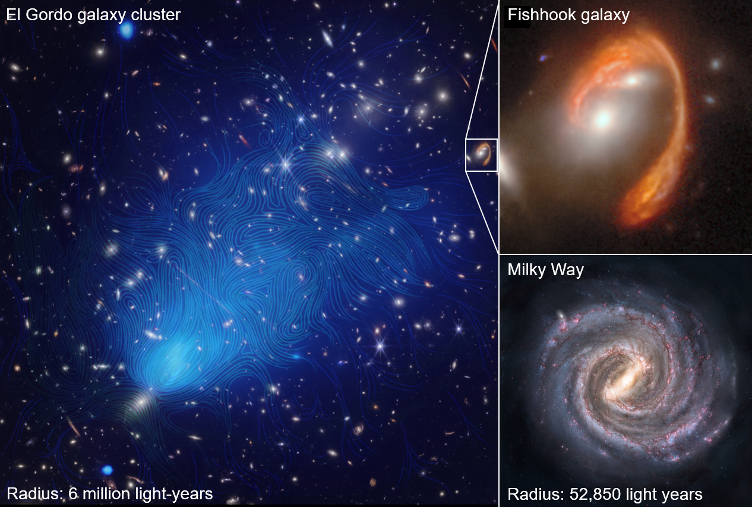

However, mapping the magnetic fields on the scale of galaxy clusters posed a formidable challenge. The vast distances and complex interactions with magnetized and turbulent plasmas diminish the polarization signal, a traditionally used informant of magnetic fields. Here, the groundbreaking technique — synchrotron intensity gradients (SIG) — developed by a team of UW–Madison astronomers and physicists led by astronomy professor Alexandre Lazarian, marks a turning point. They shifted the focus from polarization to the spatial variations in synchrotron intensity. This innovative approach peels back layers of cosmic mystery, offering a new way to observe and comprehend the all-important magnetic tapestry on scale of millions of light years.

A landmark study published in Nature Communications has employed the SIG technique to unveil the enigmatic magnetic fields within five colossal galaxy clusters, including the monumental El Gordo cluster, observed with the Very Large Array (VLA) and MeerKAT telescope. This colossal cluster, formed 6.5 billion years ago, represents a significant portion of cosmic history, dating back to nearly half the current age of the universe. The findings in El Gordo, characterized by the largest magnetic fields observed, provide crucial insights into the structure and evolution of galaxy clusters.

The research is a fruitful collaboration between the UW–Madison team and their Italian colleagues, including Gianfranco Brunetti, Annalisa Bonafede, and Chiara Stuardi from the Instituto do Radioastronomia (Bologna, Italy) and the University of Bologna. Brunetti, a renowned expert in the high-energy physics of galaxy clusters, is enthusiastic about the potential that the SIG technique holds for exploring magnetic field structures on even larger scales, such as the Megahalos recently discovered by him and his colleagues.

Echoing this excitement is the study’s lead researcher, physics graduate student Yue Hu.

“This research marks a significant milestone in astrophysics,” Hu says. “Utilizing the SIG method, we’ve observed and begun to comprehend the nature of magnetic fields in galaxy clusters for the first time. This breakthrough heralds new possibilities in our quest to unravel the mysteries of the universe.”

This study lays the groundwork for future explorations. With the SIG method’s proven effectiveness, scientists are optimistic about its application to even larger cosmic structures that have been detected recently with the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), promising deeper insights into the mysteries of the Universe magnetism and its effects on the evolution of the Universe Large Scale Structure.