Theoretical plasma astrophysicist Vladimir Zhdankin ‘11, PhD ’15, returns to UW–Madison as an assistant professor of physics on January 1, 2024. As a student, Zhdankin worked with Prof. Stas Boldyrev on solar wind turbulence and basic magnetohydrodynamic turbulence, which are relevant for near-Earth types of space plasmas. After graduating, Zhdankin began studying plasma astrophysics of more extreme environments. He first completed a postdoc at CU-Boulder, then a NASA Einstein Fellowship at Princeton University. He joins the department from the Flatiron Institute in New York, where he is currently a Flatiron Research Fellow.

Please give an overview of your research.

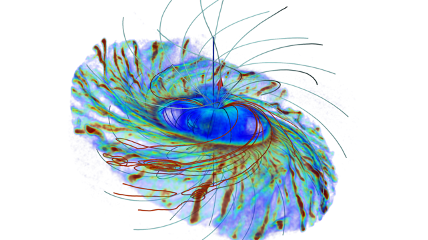

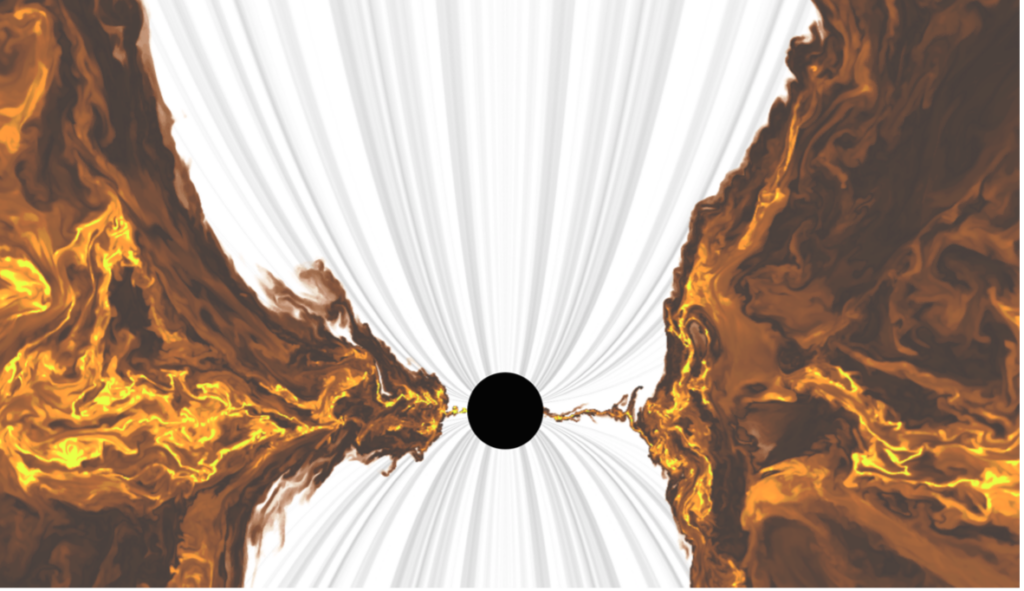

These days, most of my interest is in the field of plasma astrophysics — the application of plasma physics to astrophysical problems. Much of the matter in the universe is in a plasma state, such as stars, the matter around black holes, and the interstellar medium in the galaxy. I’m interested in understanding the plasma processes in those types of systems. My focus is particularly on really high energy systems, like plasmas around black holes or neutron stars, which are dense objects where you could get extreme plasmas where relativistic effects are important. The particles are traveling at very close to the speed of light, and there’s natural particle acceleration occurring in these systems. They also radiate intensely, you could see them from halfway across the universe. There’s a need to know the basic plasma physics in these conditions if you want to interpret observations of those systems. A lot of my work involves doing plasma simulations of turbulence in these extreme parameter regimes.

What are one or two research projects you’ll focus on the most first?

One of them is on making reduced models of plasmas by using non-equilibrium statistical mechanical ideas. Statistical mechanics is one of the core subjects of physics, but it doesn’t really seem to apply to plasmas very often. This is because a lot of plasmas are in this regime that’s called collisionless plasma, where they are knocked out of thermal equilibrium, and then they always exist in a non-thermal state. That’s not what standard statistical mechanics is applicable to. This is one of the problems that I’m studying, whether there is some theoretical framework to study these non-equilibrium plasmas, to understand basic things like: what does it mean for entropy to be produced in these types of plasmas? The important application of this work is to explain how are particles accelerated to really high energies in plasmas. The particle acceleration process is important for explaining cosmic rays which are bombarding the Earth, and then also explaining the highest energy radiation which we see from those systems.

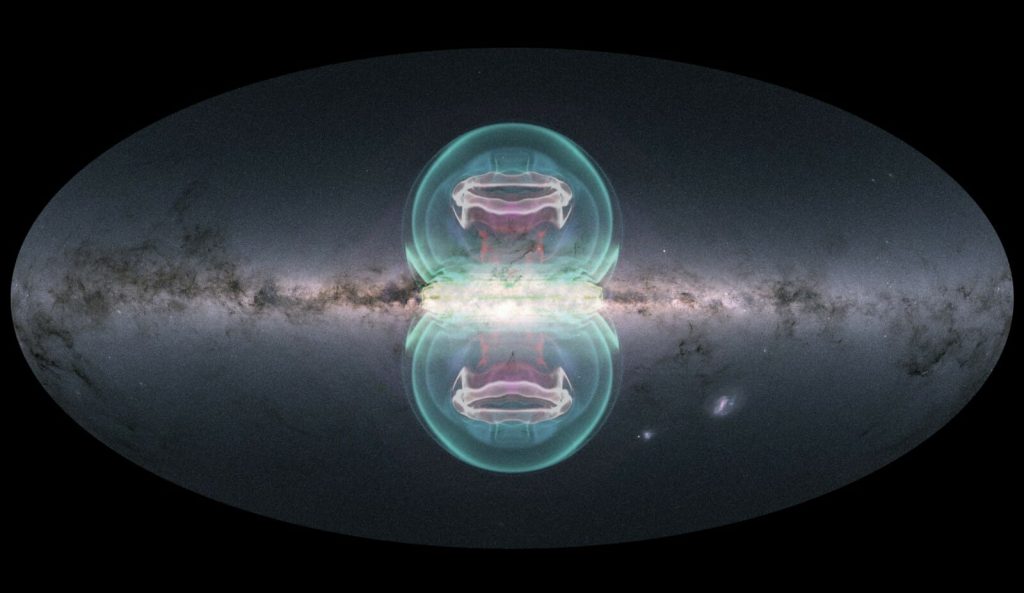

Another thing I’m thinking about these days is plasmas near black holes. In the center of the Milky Way, for example, there’s a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A*, which was recently imaged a year or two ago by the Event Horizon Telescope. It’s a very famous picture. What you see is the shape of the black hole and then all the plasma in the vicinity, which is in the accretion disk. I’m trying to understand the properties of that turbulent plasma and how to model the type of radiation coming out of the system. And then also whether we should expect neutrinos to be coming out, because you would need to get very high energy protons in order to produce neutrinos. And it’s still an open question of whether or not that happens in these systems.

What attracted you to UW–Madison?

It’s just a perfect match in many ways. It really feels like a place where I’m confident that I could succeed and accomplish my goals, be an effective mentor, and build a successful group. It has all the resources I need, it has the community I need as a plasma physicist to interact with. I think it has a lot to offer to me and likewise, I have a lot to offer to the department there. I’m also really looking forward to the farmers’ market and cheese and things like that. You know, just the culture there.

What is your favorite element and/or elementary particle?

I like the muon. It is just a heavy version of the electron, I don’t remember, something like 100 times more massive or so. It’s funny that such particles exist and this is like the simplest example of one of those fundamental particles which we aren’t really familiar with, it’s just…out there. You could imagine situations where you just replace electron with a muon and then you get slightly different physics out of it.

What hobbies and interests do you have?

They change all the time. But some things I’ve always done: I like running, skiing, bouldering indoors, disk golf, racquet sports, and hiking. (Cross country or downhill skiing?) It’s honestly hard to choose which one I prefer more. In Wisconsin, definitely cross country. If I’m in real mountains, the Alps or the Rockies, then downhill is just an amazing experience.