Detecting a chemical change is often easy: colors may change, heat may be released, or something may smell different. Seeing reactions at the molecular level is not quite so easy, but knowing exactly when and how chemical bonds form or atoms move around is crucial to understanding chemical processes.

In a new study published March 15 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, University of Wisconsin–Madison physics professor Uwe Bergmann and his collaborators have turned ultrafast x-ray pulses into something more akin to an optical laser, with cleaner, directional pulses. Their work may lead to visualizing chemical reactions faster than ever at the atomic scale.

“This work is the first step to do with x-rays the same kind of [techniques] which you do with regular lasers,” says Bergmann, the study’s senior author. “We have opened a time window for looking at chemical processes with attosecond [one billionth of one billionth of a second] precision. It’s a new frontier.”

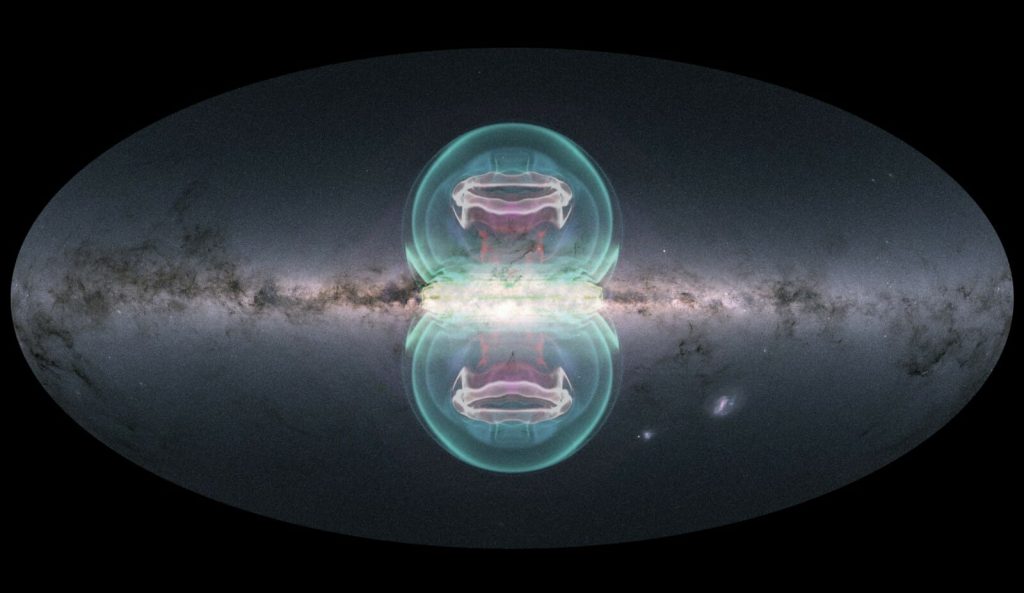

Around a decade ago, researchers began using powerful x-ray free-electron lasers, which allow them to make ultrafast movies of molecular changes in real time on the femtosecond scale (one thousand times slower than an attosecond). Compared to visible lasers, which provide clean, single-wavelength beams of light, x-ray lasers are somewhat dirty: they contain multiple wavelengths of light of randomly varying intensity.

“What all scientists have done, and are still doing, is that you just adapt to what you get and then you design your experiments around them,” Bergmann says. “That also means that certain experiments, which in the optical laser regime are now standard, have not been possible.”

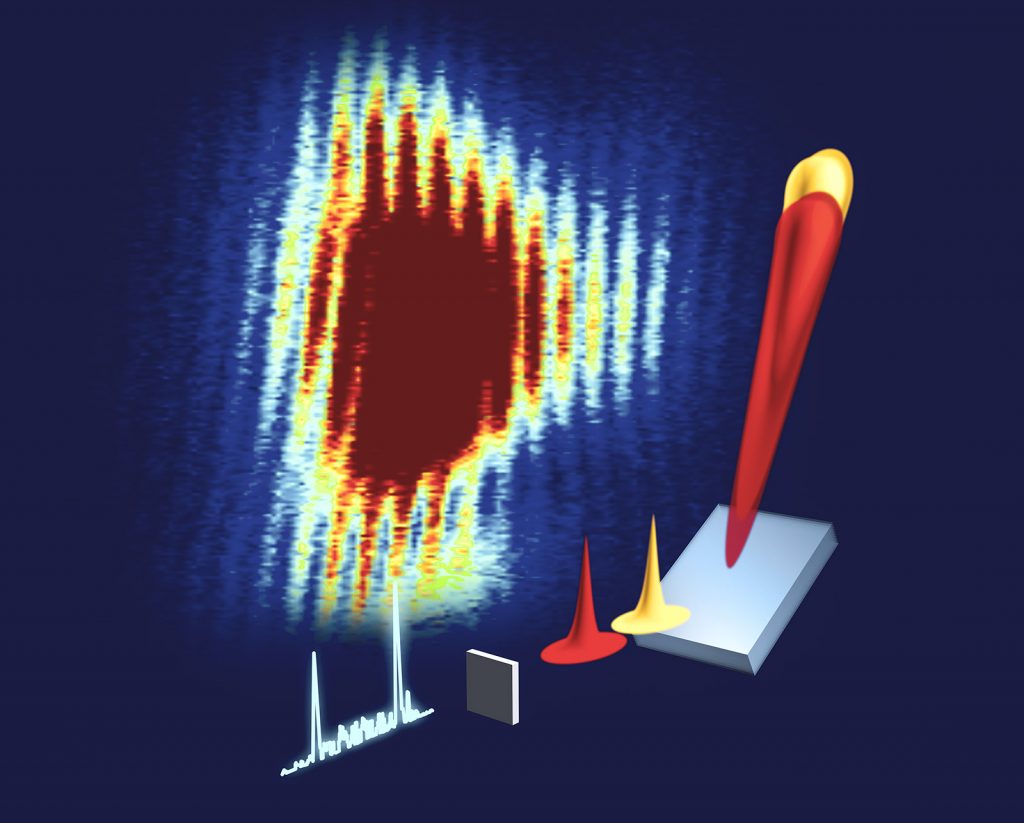

Bergmann and his colleagues somewhat accidentally discovered a way to make x-rays more like an optical laser. In their experimental setup, they shine intense but dirty x-ray pulses at a manganese sample. When these pulses hit a manganese atom, a lower-level electron is ejected and the hole it leaves is rapidly filled by a higher-level electron. The energy difference is emitted as a photon of a characteristic color. Very intense pulses can create enough of these holes. An emitted photon can effectively stimulate the emission of another one, leading to an avalanche of stimulated X-ray emission, mostly in the forward direction towards their detector.

Every so often, the detector that captures these stimulated emissions showed something they were not expecting: strong fringes, the characteristic pattern that results from constructively and destructively interfering signals. The fringes suggested that they had observed two x-ray emission pulses, separated by only a few femtoseconds.

“We were confused,” Bergmann says. “How did such a pair of x-ray pulses come about?”

After many discussions, calculations, and simulations, the team ruled out many possible explanations, until they finally realized what had happened: occasionally, two of the many spikes in the dirty pulses were much stronger than the rest of them. When these strong spikes occurred a few femtoseconds apart, and each had enough intensity, a clean pair of stimulated x-ray emission pulses emerged.

Before these two pulses reach the detector, they first travel through a monochromator — essentially a prism that stretches light, much like how white light passing through a clear prism is stretched into a rainbow. These stretched pulses then overlap timewise, and those frequencies that are in phase with each other can add up to become more intense or cancel each other out into dark troughs. Hence, the fringes.

“At times, each signal is rather clean and of similar strength, and one obtains very strong interference fringes,” Bergmann says. “We know that the fringe spacings are directly related to the time difference of the two pulses, and because we can measure them very precisely, we can obtain their time difference with extreme, attosecond precision.”

Currently, these pulse pairs are generated very rarely, Bergmann and his collaborators will work with the accelerator scientists to find ways to manipulate the ‘dirty’ pulses and enhance the chance of producing the pairs. They are optimistic that their work opens the door to new applications of such x-ray pulse pairs — the types of techniques that are used commonly with visible laser light.

“We’re trying to move nonlinear laser optics into the x-ray regime,” Bergmann says. “In the x-ray regime, you can probe certain phenomena that you just cannot optically access. X-ray wavelengths are comparable to the distances between atoms, and we can knock out lower-level electrons to get element specificity with them.”

—

Bergmann’s contribution to this research was funded in part by the U.S. Department of Energy, Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (DE-AC02-76SF00515). Other authors were supported by various funding as described in the study.