This story was originally published by the Chicago Quantum Exchange

Qubits are the building blocks of quantum computers, which have the potential to revolutionize many fields of research by solving problems that classical computers can’t.

But creating qubits that have the perfect quality necessary for quantum computing can be challenging.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, HRL Laboratories LLC, and University of New South Wales (UNSW) collaborated on a project to better control silicon quantum dot qubits, allowing for higher-quality fabrication and use in wider applications.

All three institutions are affiliated with the Chicago Quantum Exchange. The work was published in Physical Review Letters, and the lead author, J. P. Dodson, has recently transitioned from UW–Madison to HRL.

“Consistency is the thing we’re after here,” says Mark Friesen, Distinguished Scientist of Physics at UW–Madison and author on the paper. “Our claim is that there is actually hope to create a very uniform array of dots that can be used as qubits.”

Sensitive quantum states

While classical computer bits use electric circuits to represent two possible values (0 and 1), qubits use two quantum states to represent 0 and 1, which allows them to take advantage of quantum phenomena like superposition to do powerful calculations.

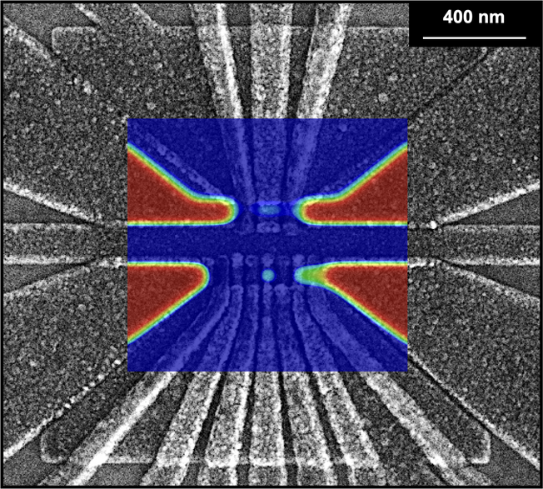

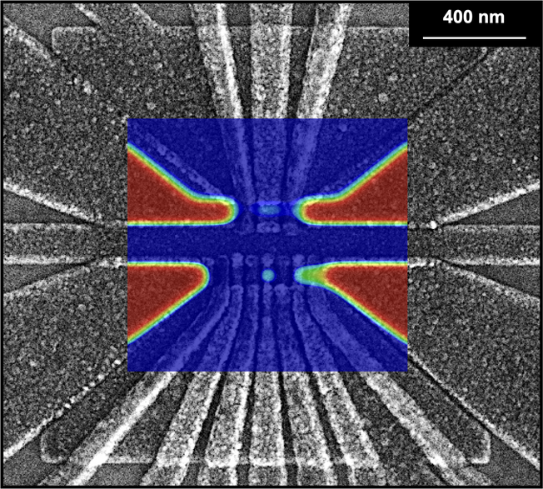

Qubits can be constructed in different ways. One way to build a qubit is by fabricating a quantum dot, or a very, very small cage for electrons, formed within a silicon crystal. Unlike qubits made of single atoms, which are all naturally identical, quantum dot qubits are man-made—allowing researchers to customize them to different applications.

But one common wrench in the metaphorical gears of these silicon qubits is competition between different kinds of quantum states. Most qubits use “spin states” to represent 0 and 1, which rely on a uniquely quantum property called spin. But if the qubit has other kinds of quantum states with similar energies, those other states can interfere, making it difficult for scientists to effectively use the qubit.

In silicon quantum dots, the states that most often compete with the ones needed for computing are “valley states,” named for their locations on an energy graph—they exist in the “valleys” of the graph.

To have the most effective quantum dot qubit, the valley states of the dot must be controlled such that they do not interfere with the quantum information-carrying spin states. But the valley states are extremely sensitive; the quantum dots sit on a flat surface, and if there is even one extra atom on the surface underneath the quantum dot, the energies of the valley states change.

The study’s authors say these kinds of single-atom defects are pretty much “unavoidable,” so they found a way to control the valley states even in the presence of defects. By manipulating the voltage across the dot, the researchers found they could physically move the dot around the surface it sits on.

“The gate voltages allow you to move the dot across the interface it sits on by a few nanometers, and by doing that, you change its position relative to atomic-scale features,” says Mark Eriksson, John Bardeen Professor and chair of the UW–Madison physics department, who worked on the project. “That changes the energies of valley states in a controllable way.

“The take home message of this paper,” he says, “is that the energies of the valley states are not determined forever once you make a quantum dot. We can tune them, and that allows us to make better qubits that are going to make for better quantum computers.”

Building on academic and industry expertise

The host materials for the quantum dots are “grown” with precise layer composition. The process is extremely technical, and Friesen notes that Lisa Edge at HRL Laboratories is a world expert.

“It requires many decades of knowledge to be able to grow these devices properly,” says Friesen. “We have several years of collaborating with HRL, and they’re very good at making really high-quality materials available to us.”

The work also benefitted from the knowledge of Susan Coppersmith, a theorist previously at UW–Madison who moved to UNSW in 2018. Eriksson says the collaborative nature of the research was crucial to its success.

“This work, which gives us a lot of new knowledge about how to precisely control these qubits, could not have been done without our partners at HRL and UNSW,” says Eriksson. “There’s a strong sense of community in quantum science and technology, and that is really pushing the field forward.”