This story was originally published by the OVCR

The Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research (OVCR) hosts the Research Forward initiative to stimulate and support highly innovative and groundbreaking research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The initiative is supported by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) and will provide funding for 1–2 years, depending on the needs and scope of the project.

Research Forward seeks to support collaborative, multidisciplinary, multi-investigator research projects that are high-risk, high-impact, and transformative. It seeks to fund research projects that have the potential to fundamentally transform a field of study as well as projects that require significant development prior to the submission of applications for external funding. Collaborative research proposals are welcome from within any of the four divisions (Arts & Humanities, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, Social Sciences), as are cross-divisional collaborations.

Physics professor Mark Saffman is part of a team awarded funding in Round 4 of the Research Forward competition for their project:

Quanta sensing for next generation quantum computing

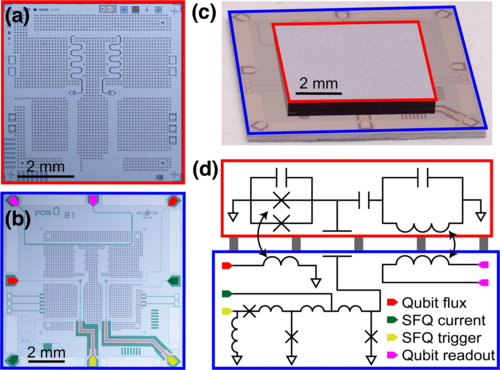

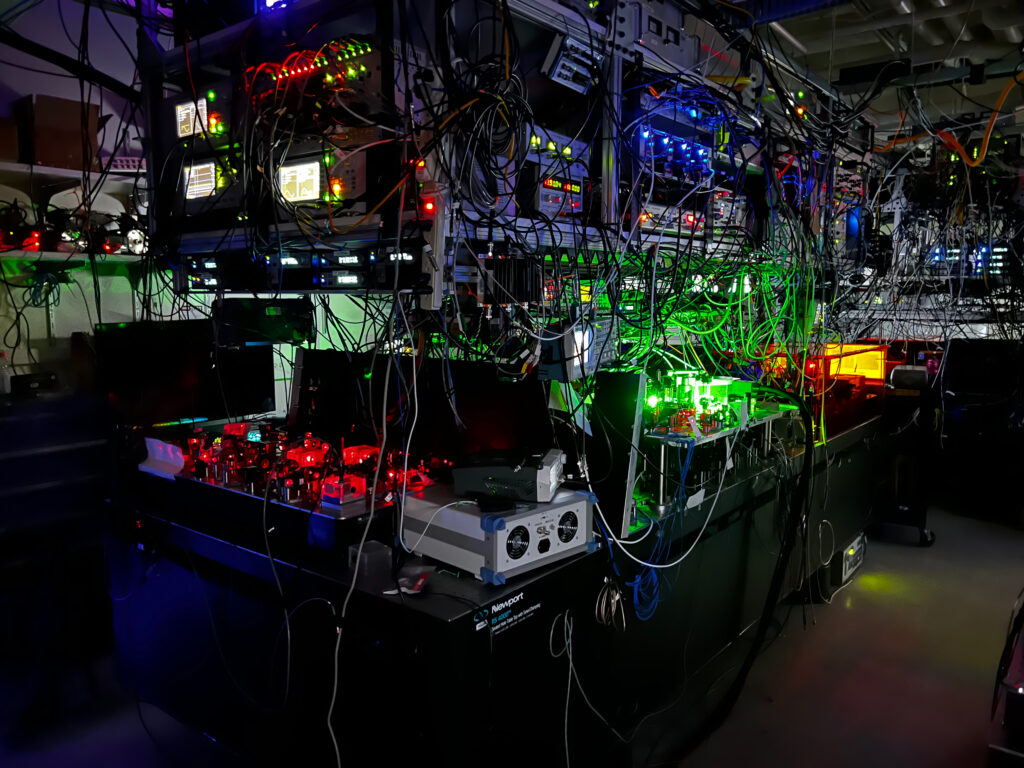

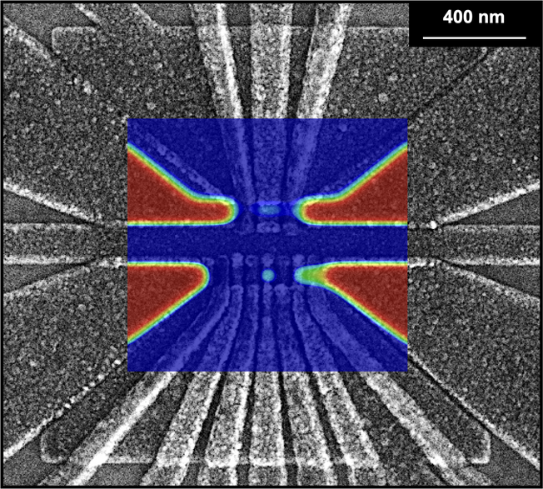

Future quantum computers could open new scientific and engineering frontiers, impacting existential challenges like climate change. However, quantum information is delicate; it leaks with time and is prone to significant errors. These errors are exacerbated by imperfect reading and writing of quantum bits (qubits). These challenges fundamentally limit our ability to run quantum programs, and could hold back this powerful technology. Fast and accurate qubit readout, therefore, is essential for unlocking the quantum advantage. Current quantum computers use conventional cameras for reading qubits, which are inherently slow and noisy.

This research project will use quanta (single-photon) sensors for fast and accurate qubit readout. Quanta sensors detect individual photons scattered from qubits, thus enabling sensing qubits at 2-3 orders of magnitude higher speeds (few microseconds from ~10 milliseconds), thereby transforming the capabilities (speed, accuracy) of future quantum computers, and for the first time, paving the way for scalable and practical quantum computing.

Principal investigator: Mohit Gupta, associate professor of computer sciences

Co-PIs: Mark Saffman, professor of physics; Swamit Tannu, assistant professor of computer sciences; Andreas Velten, associate professor of biostatistics and medical informatics, electrical and computer engineering