Ten years ago, on July 4, 2012, the CMS and ATLAS collaborations at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN — including many current and former UW–Madison physicists — announced they had discovered a particle that was consistent with predictions of the Higgs boson.

In the ten years since, scientists have confirmed the finding was the Higgs boson, but its discovery opened more avenues of discovery than it closed. Now, with the LHC back up and running, delivering proton collisions at unprecedented energies, high energy physicists are ready to investigate even more properties of the particle.

“The Higgs plays an incredibly important role in particle physics,” says Kevin Black, who previously worked on ATLAS before joining the UW–Madison physics department and is now part of CMS. “But for being such a fundamental particle, for giving mass to all elementary particles, for being deeply connected to flavor physics and why we have different generations of matter particles — we know a relatively small amount about it.”

Finding the Higgs particle had been one of the main goals of the LHC. The particle was first theorized by physicist Peter Higgs (amongst others, but his name was forever associated with it) in the 1960s.

“The basic idea was that if you just had electromagnetic and strong interactions, then the theory would have been fine if you just put a mass in by hand for the elementary particles,” explains Black. “The weak interaction spoils that, and it was a big question at the time of whether or not the whole structure of particle physics and of quantum field theory were actually going to be consistent.”

Higgs and others realized that there was a way to make it happen if they introduced a new field, which then became the Higgs field and the Higgs particle, that can interact with all other matter and give particles their mass. The Higgs particle, however, eluded experimental observation, leaving a gap in the Standard Model. In retrospect, one of the difficulties was that the mass of the Higgs — around 125 GeV — was much larger than the technology at the time could reach experimentally.

In earlier generations of experiments, UW–Madison physicist Sau Lan Wu participated in searches using the ALEPH experiment that placed a strong lower bound on the mass of the Higgs boson. Also at UW–Madison, Duncan Carlsmith, Matthew Herndon and their groups participated in searches at the CDF experiment that placed an upper bound on the mass of the Higgs boson and saw evidence of Higgs production in the region of mass where it was finally discovered.

This research set the stage for the experiments that were perfectly designed to discover the Higgs boson: the world’s most powerful hadron collider, the LHC, and the most capable pair of high energy collider experiments ever built, CMS and ATLAS.

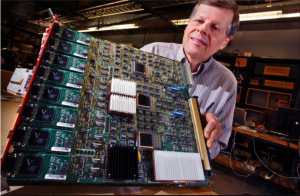

The UW–Madison CMS group had three major projects: the trigger project led by Wesley Smith (now emeritus faculty), and the end cap muon system led by Don Reeder (now emeritus faculty) and Dick Loveless (now emeritus scientist), and a computing project led by Sridhara Dasu, who is current head of the group. Having made essential detector contributions, the UW–Madison CMS group, including Herndon, moved on to Higgs hunting and the discoveries. The group, now bolstered by the addition of Black and Tulika Bose to the physics department faculty, continues the work of understanding the Higgs Boson thoroughly.

The UW–Madison ATLAS group, founded and led by Wu, is an important leader of Higgs physics. The group is fortunate to attract another important leader of ATLAS, Higgs physicist Kyle Cranmer, who recently joined UW–Madison as physics department faculty and the director of the American Family Data Science Institute.

Both CMS and ATLAS announced the discovery, made separately but concurrently, in 2012. When it was first discovered, it conformed to expected energies and momentum of the Higgs, but finding it in this rare decay mode was unexpected, so LHC scientists called it the Higgs-like particle for a while.

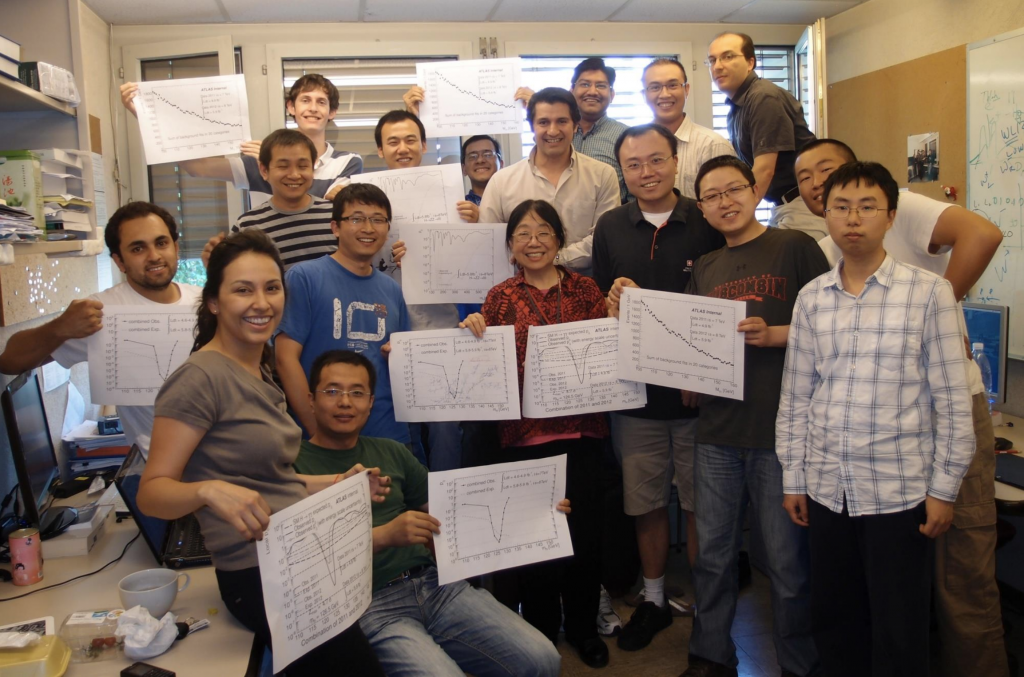

Wu recalls her and her group’s involvement in a recent essay published in Physics Today:

At 3:00pm [on June 25, 2012], there was a commotion in the Wisconsin corridor on the ground floor of CERN Building 32. My graduate student Haichen Wang was saying loudly, ‘Haoshuang is going to announce the Higgs discovery!’ Our first reaction was that it was a joke; thus when we entered Haoshuang’s office, we all had smiles on our faces. Those smiles suddenly became much bigger when we got to look at the result of Haoshuang’s combination: It showed the 5.08s close to the Higgs mass of 125GeV/c2. Pretty soon, cheers were ringing down the Wisconsin corridor.

ATLAS had a discovery!”

The Higgs-like announcement from ten years ago has since been confirmed to be the Higgs particle. Several years later, Dasu’s group’s work saw the Higgs decay into the tau, and provided the first evidence of the particle coupling to matter particles, not just to bosons.

On the ten-year anniversary, both ATLAS and CMS collaborations published summaries of their findings to date and future directions. Experimental questions still being addressed include continuing to measure higher-precision interactions between the Higgs and particles it has already been observed to interact with, and detecting previously-unobserved interactions between the Higgs and other particles.

“One big question that immediately comes to my mind is the mass problem. The breakthrough generated by the Higgs discovery was that elementary particles acquire their masses through the Higgs particle,” Wu writes in her Physics Today essay. “A deeper question that needs to be answered is how to explain the values of the individual masses of the elementary particles. In my mind, this mass problem remains a big topic to be explored in the years to come.”

“Another one of the big things that we’re looking for in future data is to understand Higgs potential,” Black says. “Right now, by measuring the mass, we’ve only measured right around its ground state, and that has great implications for the stability of our universe.”

Also on the ten-year anniversary, CERN announced that the LHC — which had been shut down for three years to work on upgrades — was ready to again start delivering proton collisions at an unprecedented energy of 13.6 TeV in its third round of runs. It is expected that the ATLAS and CMS detectors will record more collisions in this upcoming run than in the previous two combined.

The LHC program is scheduled to run through 2040, and the UW–Madison scientists who are part of the CMS and ATLAS collaborations will almost certainly continue to play key roles in future discoveries.

UW–Madison’s current CMS collaboration members include Kevin Black, Tulika Bose, Sridhara Dasu, and Matthew Herndon, and their research groups. Current ATLAS collaboration members include Kyle Cranmer and Sau Lan Wu and their research groups.