Read the full article at:

https://chicagoquantum.org/news/wonders-quantum-physics-program-inspires-next-generation-scientists-classroom-kits

Read the full article at:

https://chicagoquantum.org/news/wonders-quantum-physics-program-inspires-next-generation-scientists-classroom-kits

Year: 2025

Deniz Yavuz elected Fellow of the American Physical Society

Congratulations to Prof. Deniz Yavuz, who was elected a 2025 Fellow of the American Physical Society!

He was elected “for outstanding experimental and theoretical contributions to nanoscale localization of atoms with electromagnetically induced transparency and collective radiation effects in atomic ensembles,” and nominated by the Division of Atomic, Molecular & Optical Physics (DAMOP).

APS Fellowship is a distinct honor signifying recognition by one’s professional peers for outstanding contributions to physics. Each year, no more than one half of one percent of the Society’s membership is recognized by this honor.

See the full list of 2025 honorees at the APS Fellows archive.

Nobel Prize in Physics has ties to UW–Madison-incubated company

Vladimir Zhdankin earns DOE Early Career award

Congrats to Vladimir Zhdankin, assistant professor of physics, on earning a Department of Energy Early Career award! The five-year award will fund his research on energy and entropy in collisionless, turbulent plasmas.

Systems in equilibrium are easy to describe, but often the most interesting questions in nature are complex and dynamic. Most plasmas, including astrophysical ones and manmade ones on earth, are not in equilibrium, so they are more difficult to characterize. Zhdankin’s research is working toward a more universal understanding of non-equilibrium plasmas, in the form of mathematical equations that can then be broadly applied.

“We think that our understanding of plasmas isn’t finished yet, and there are still some basic ingredients in the statistical mechanics which, once we understand better, we’ll have a more predictive framework for how plasmas should behave,” Zhdankin says.

Collisionless plasmas have a low enough particle density where the particles largely flow without bumping into each other. Instead, their trajectories are controlled by the electric and magnetic field, which leads to a generally chaotic flow, like the rapids of a river. It is that dynamic turbulence that causes these plasmas to be non-equilibrium, leading to interesting, if not straightforward, properties.

“In these systems, energy is conserved — it has to be,” Zhdankin says. “But we don’t quite have a handle on what’s happening with the entropy. We have reason to believe it’s increasing, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics, but it doesn’t seem to reach a maximum.”

Zhdankin’s goal is to better understand the energy and entropy in these complex plasmas through “particle-in-cell” simulations, where tens of billions of plasma particles — electrons and protons — are simulated in a small box, then manipulated in various ways.

“We imagine stirring the plasma to make it more turbulent and putting some energy into it, and then we want to see how it heats up and how the particles achieve higher energies,” Zhdankin says. “What if we increase or decrease the size of the box? Make the magnetic field stronger? Make the particles collide a little bit?”

The simulations can then be compared to real-world data, including measurements of the solar wind or laboratory plasmas. An ideal outcome would be obtaining formulae that better describe these complex, turbulent plasmas and can be applied across a broad range of systems, from laboratory experiments to the accretion flows of black holes.

“And there’s a chance we’re just not going to be able to get something predictive out of this work, if there’s just too big of a landscape of possibilities,” Zhdankin says. “But this topic, I consider it one of the most fundamental ones that could be studied in plasma physics.”

With major U.S. investment, UW-Madison leads effort to advance abundant fusion energy for all

Double the Higgs, Double the Mystery! The hunt for a new, heavy particle decaying to a pair of Higgs Bosons

This story, written by physics grad student Ganesh Parida, was originally published by the CMS collaboration

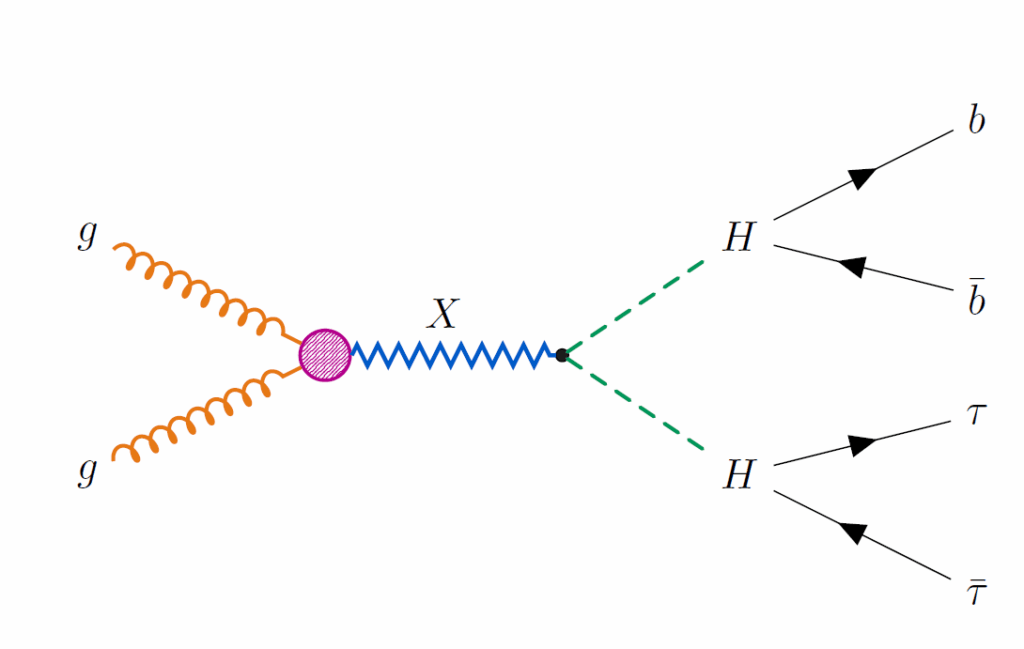

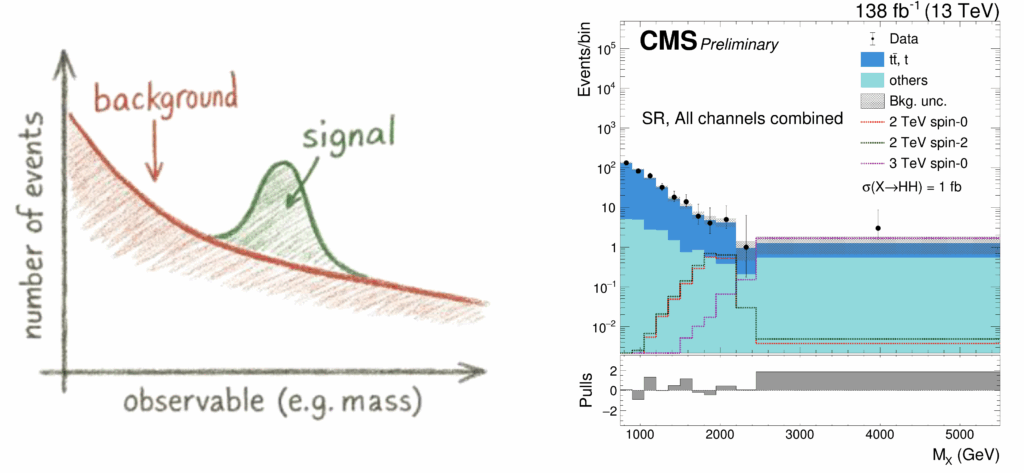

CMS scientists are on the hunt for a new, heavy particle that decays into a pair of Higgs bosons. Using the final state with two bottom quarks and two tau leptons, the search sets the most stringent limits to date in the mass range 1.4–4.5 TeV.

The CMS experiment is searching for signs of new, heavy particles that could decay into pairs of Higgs bosons – we call this an HH signature. These signatures are particularly exciting because they can give us clues about the stability of our universe and open a window to physics beyond our current understanding of fundamental particles and their interactions, the standard model.

In this search, we focus on a final state where one Higgs boson decays to two bottom quarks (H→bb) and the other decays to two tau leptons (H→ττ). This final state offers a promising balance: it has a relatively large probability of occurring, while also allowing us to separate signal events from background processes. Performing such a search is far from straightforward. If a new heavy particle were produced at the LHC, it would impart a large momentum, a “boost”, to its daughter Higgs bosons. The boost causes the decay products of each Higgs boson to be collimated and overlap in the detector, making their reconstruction quite challenging.

To meet this challenge, CMS uses advanced reconstruction and machine-learning techniques. For the H→bb decay, the bottom quarks form collimated sprays of particles, called jets, which overlap to a large extent. To identify them, a graph neural network, called ParticleNet, is trained to recognize the pattern of the two bottom quark jets inside a single, large jet.

Reconstructing the H→ττ is a two-step process: first, we untangle and reconstruct the two really close taus, and then we use a convolutional neural network, called Boosted DeepTau to figure out the characteristics of these reconstructed taus and tell them apart from background jets. Because tau leptons also produce invisible neutrinos, we apply a likelihood-based method to obtain the four-momentum of the parent Higgs boson.

Once both Higgs bosons are reconstructed, we can combine them to measure the mass of the system. If a new heavy particle exists, it would appear as a peak, or “bump,” on top of the smoothly falling background distribution. This strategy is often referred to as a “bump hunt” – a classic tool in the search for new particles at colliders.

After analyzing data from the full LHC Run 2 (2016–2018), CMS did not observe any significant deviation from the standard model prediction. While this means that no new particle was discovered in this final state yet, the analysis sets the most stringent upper limits to date on the possible production of heavy particles decaying into Higgs boson pairs in the bbττ final state in the mass range of 1.4 TeV to 4.5 TeV.

“The results may not yet show evidence of new physics, but they are paving the way,” says Ganesh Parida, a PhD student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, who carried out this analysis together with Camilla Galloni and Deborah Pinna, both scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and members of CMS. “It has been both exciting and rewarding to learn, develop, and apply sophisticated techniques to probe these challenging boosted regimes.”

The biggest challenge here is the sheer number of events we can collect for these difficult “boosted” scenarios. That is why the ongoing Run 3 and the upcoming High-Luminosity runs of the LHC are so important – they will give us the biggest datasets ever for a potential discovery!

Quantum Computing Could Be a $1 Trillion Revolution—And Wisconsin Is in the Race

UW–Madison team awarded NSF grant to develop cameras for the world’s largest high-energy gamma-ray observatory

This story was adapted from the WashU and CTAO releases for the University of Wisconsin–Madison. A team of researchers and engineers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Washington University in St. Louis has been awarded a $3.9 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation to build and install gamma-ray cameras for the Cherenkov Telescope [...]

Read the full article at: https://wipac.wisc.edu/uw-madison-team-awarded-nsf-grant-to-develop-cameras-for-the-worlds-largest-high-energy-gamma-ray-observatory/Hilldale Undergraduate Award Winners in Physics

Four physics majors have earned 2025 Hilldale Fellowships. They are:

- Ruben Aguiló Schuurs, Computer Sciences and Physics major, working with Mark Saffman

- Zijian Hao, Astronomy – Physics and Physics major, working with Paul Terry (Physics)

- Nathaniel Tanglin, Astronomy – Physics and Physics major, working with Elena D’Onghia (Astronomy)

- Michael Zhao, AMEP and Physics major, working with Saverio Spagnolie (Mathematics)

Additionally, Qing Huang, a Data Science, Information Science, and Statistics major working with Gary Shiu (Physics) also earned an award.

The Hilldale Undergraduate/Faculty Research Fellowship provides research training and support to undergraduates. Students have the opportunity to undertake their own independent research project under the mentorship of UW–Madison faculty or research/instructional academic staff. Please Note: Graduate students are ineligible to serve as the project advisor. Approximately 97 – 100 Hilldale awards are available each year.

The student researcher receives a $4,000 stipend (purpose unrestricted) and the faculty/staff research advisor receives $1,000 to help offset research costs (e.g., supplies, books for the research, student travel related to the project). The project advisor can decline the $1,000 if it is not needed to support the student’s research. Declined project advisor funds are pooled to offer additional Hilldale Fellowships.

Roman Kuzmin earns NSF CAREER Award

Congrats to Roman Kuzmin, the Dunson Cheng Assistant Professor of Physics, for being selected for an NSF CAREER award. The 5-year award will support Kuzmin and his group’s research on understanding fluxonium qubits and how their properties can be used to simulate the collective behavior of quantum materials.

Superconducting qubits are one promising technology for quantum computing, and the best-studied type is the transmon. Kuzmin’s work will investigate the fluxonium type, which he expects to be an improvement over transmons because they have demonstrated higher coherence, and their ground and first excited state are better separated from other energy levels.

“These properties make fluxonium behave similar to a magnetic moment, or like a magnetic atom, which we can fabricate in the lab and tune its properties,” Kuzmin says. “Things become interesting when interactions are very strong, and you need to involve many-body physics to describe them. We plan to build circuits which recreate the behavior of these complicated systems so that we have better control and can study multiple collective phenomena that appear in materials with magnetic impurities.”

In the lab, this research will be explored by building circuits with fluxonium qubits, capacitors, and inductors, which are further combined into more complicated circuits. The circuits will be used to test theoretical predictions of such behaviors as quantum phase transitions, entanglement scaling, and localization.

In addition to an innovative research component, NSF proposals require that the research has broader societal impacts, such as developing a competitive STEM workforce or increasing public understanding of science. Kuzmin plans to expand his work in the department’s Wonders of Physics program. This past February, he helped build a wave machine (with Steve Narf) to visually demonstrate patterns of interference, and he performed in all eight shows. His group has also participated in TeachQuantum, a summer research program for Wisconsin high school teachers run through HQAN, the NSF-funded Quantum Leap Challenge Institute that UW–Madison is a part of.

“One of the goals of this proposal is to introduce more quantum physics to the annual Wonders of Physics show; another is to provide hands-on training for high school teachers in my lab,” Kuzmin says. “Together, these activities will increase K-12 students’ engagement with quantum science and technology.”

The Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program is an NSF-wide activity that offers the Foundation’s most prestigious awards in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization. Activities pursued by early-career faculty should build a firm foundation for a lifetime of leadership in integrating education and research.