This story was originally published by University Communications

The fusion furnaces that are the universe’s stars create the elements from helium up to iron. But iron is only number 26 on the periodic table out of well over 100 known elements. So the heavier ones, like gold, lead and uranium, must come from somewhere other than fusion.

Scientists have long known that those heavy elements come from neutron capture, where neutrons are added to an element that make it unstable, then it radioactively decays and its atomic number increases by one. Nearly 70 years ago, they confirmed one site, or event, of a neutron capture method known as the slow, or s-process. The rapid, or r-process, was not confirmed with a site until 2017, when the LIGO/VIRGO collaboration detected a neutron star merger.

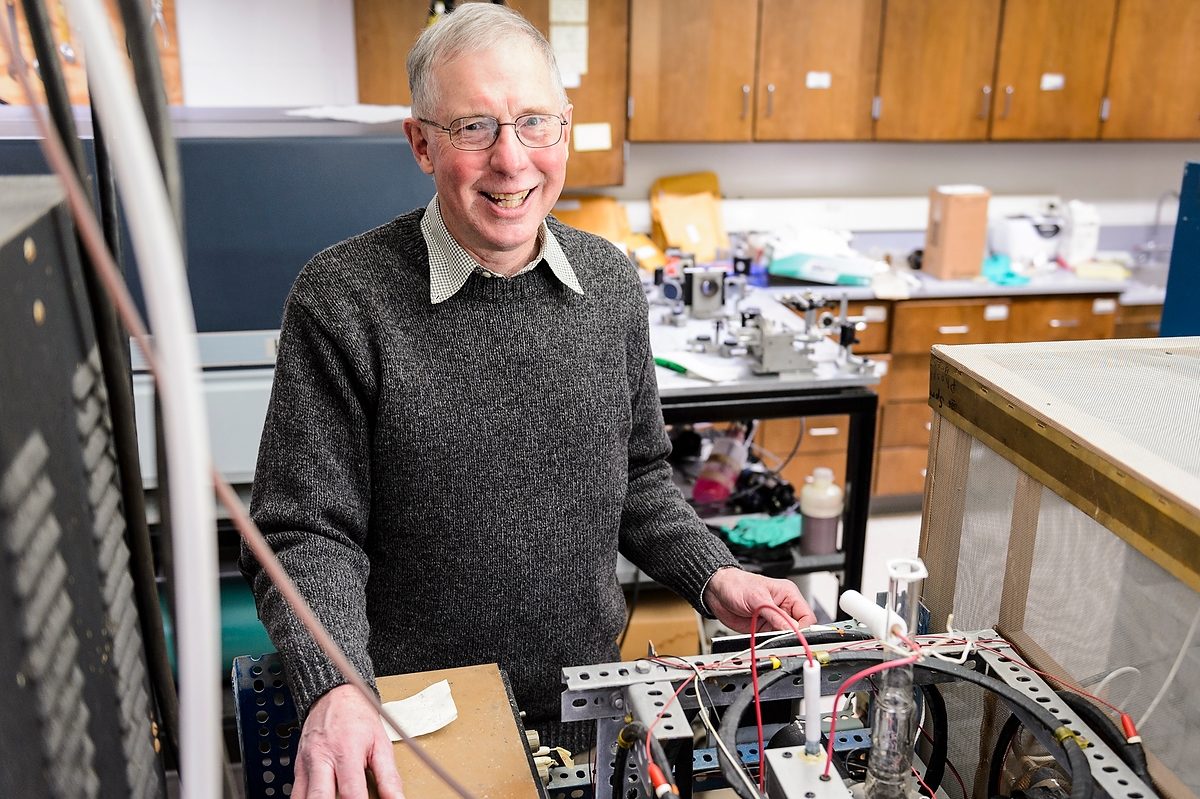

“With a neutron star merger, the neutron stars are ripped apart and they throw out neutrons, and you can build lots of heavy elements out of these neutron stars,” says Jim Lawler, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “The mystery arises when we look at the total r-process inventory of our home galaxy: Can we explain all that with neutron star mergers or are there additional sites?”

In a new study led by astronomers from the University of Michigan, Lawler and colleagues identified the elemental composition of HD 222925, a Milky Way star located over 1400 lightyears from earth. Their analysis confirmed that the star was rich in r-process elements, and they were able to identify and calculate the relative abundance of each element. They also found that the star is iron- and metal-poor, a proxy for age that indicates HD 222925 is relatively old and provides information about early star formation.

“We were able to determine a complete r-process abundance pattern for what we think is probably one event that happened early in the beginning of the universe,” Lawler says. “So that r-process template now can be used to screen various models of the nuclear physics that produce the r-process and see if the models for all sites are physically correct.”

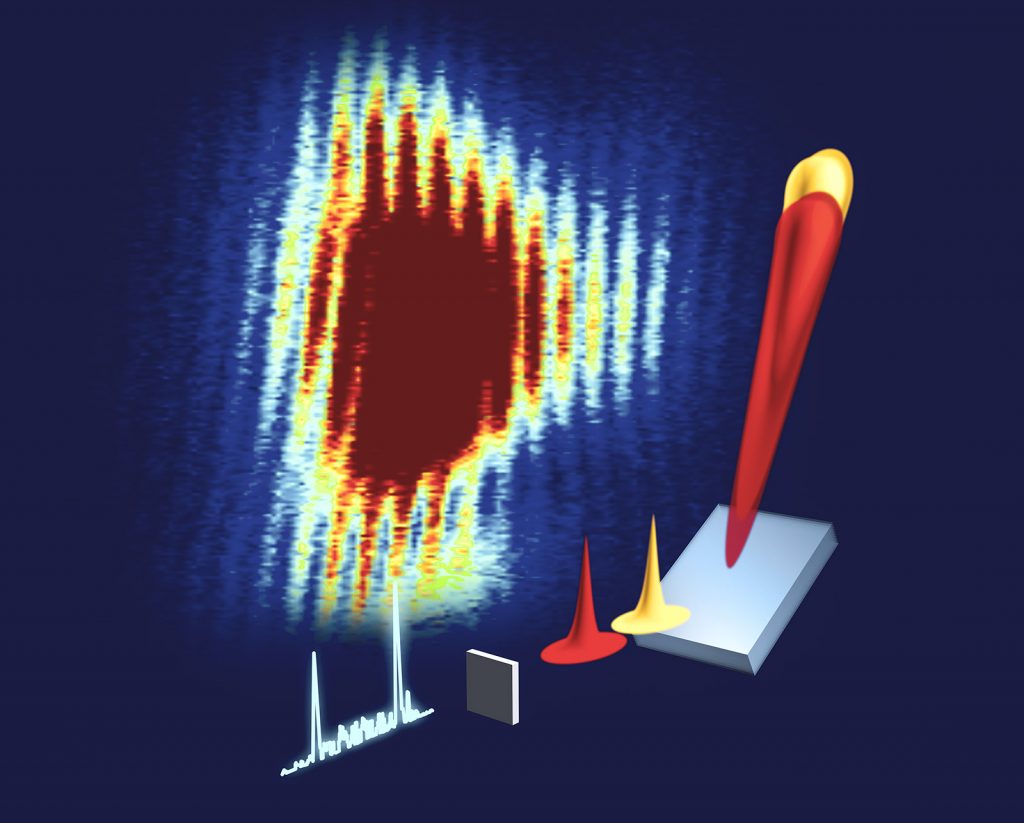

At UW–Madison, Lawler and scientist Elizabeth Denhartog contributed the spectroscopic analysis that identified the elements in the star. Every element has a unique electromagnetic spectrum that can be separated into spectral lines using a diffraction grating — just like a prism separates white light into a rainbow. HD 222925 is a relatively bright star, meaning it provided stronger spectra to analyze. It was also identified by the Hubble Space Telescope, providing access to data in the ultraviolet range that is normally blocked by the ozone layer and undetectable by telescopes on Earth.

For the full story, read more on the University of Michigan’s news site.

THIS STUDY WAS SUPPORTED IN PART BY NASA (GRANTS GO-15657, GO-15951, AND 80NSSC21K0627); U.S. NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (NSF, GRANTS PHY 14-30152, OISE 1927130, AST 1716251 AND AST 1815403); AND THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY (GRANT DE-FG02-95-ER40934); AND NOIRLAB, WHICH IS MANAGED UNDER A COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT WITH THE NSF.