In the modern, cutting-edge field of quantum computing, it can be a bit puzzling to hear a researcher relate their work to low-tech slide rules. Yet that is exactly the analogy that Roman Kuzmin uses to describe one of his research goals, creating quantum simulators to model various materials. He also studies superconducting qubits and ways to increase coherence in this class of quantum computer.

Kuzmin, a quantum information and condensed matter scientist, will join the department as an the Dunson Cheng Assistant Professor of Physics on January 1. He is currently a research scientist at the University of Maryland’s Joint Quantum Institute in College Park, Md, and recently joined us for an interview.

Can you please give an overview of your research?

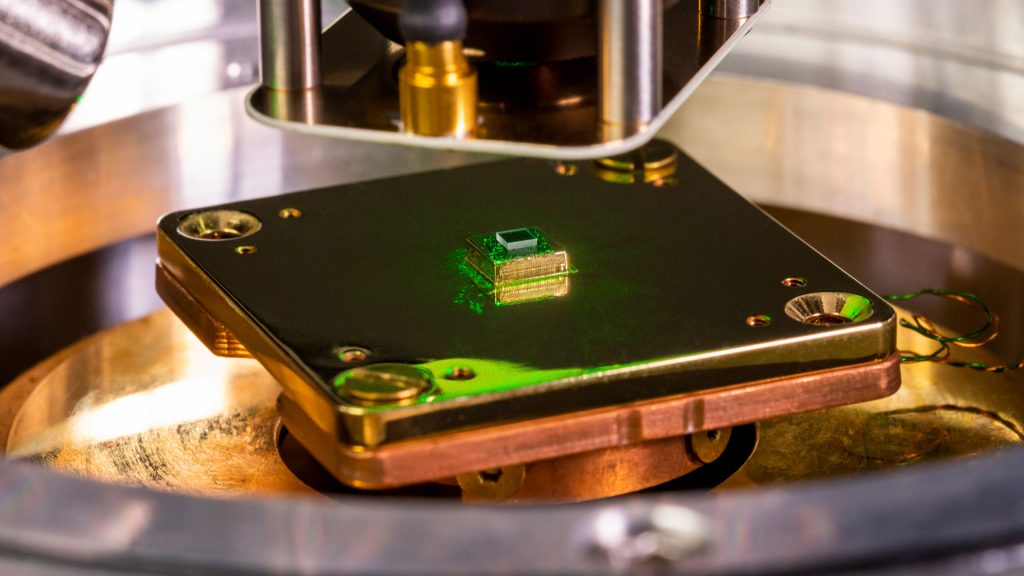

My main fields are quantum information and condensed matter physics. For example, one of my interests is to solve complicated condensed matter problems using new techniques and materials which quantum information science developed. Also, it works in the other direction. I am also trying to improve materials which are used in quantum information. I work in the subfield of superconducting circuits. There are several different directions in quantum information, and the physics department at Wisconsin has many of them already, so I will complement work in the department.

Once you’re in Madison and your lab is up and running, what are the first big one or two big things you want to really focus your energy on?

One is in quantum information and quantum computing. So, qubits are artificial atoms or building blocks of a quantum computer. I’m simplifying it, of course, but there are environments which try to destroy coherence. In order to scale up those qubits and make quantum computers larger and larger — because that’s what you need eventually to solve anything, to do something useful with it — you need to mitigate decoherence processes which basically prevent qubits from working long enough. So, I will look at the sources of those decoherence processes and try to make qubits live longer and be longer coherent.

A second project is more on the condensed matter part. I will build very large circuits out of Josephson junctions, inductors and capacitors, and such large circuits behave like some many-body objects. It creates a problem which is very hard to solve because it contains many parts, and these parts interact with each other such that the problem is much more complicated than just the sum of those parts.

What are some applications of your work?

Of course this work is interesting for developing theory and understanding our world. But the application, for example for the many-body system I just described, it’s called the quantum impurity. One of my goals is to use this to create a simulator which can potentially model some useful material. It’s like if you have a quantum computer, you can write a program and it will solve something for you. A slide rule is a physical device that allows you to do complicated, logarithmic calculations, but it’s designed to do only this one calculation. I’m creating kind of a quantum slide rule.

What is your favorite element and/or elementary particle?

So, I have my favorite circuit element: Josephson junction. (editor’s note: the question did not specify atomic element, so we appreciate this clever answer!). And for elementary particle, the photon, especially microwave photons, because that’s what I use in these circuits to do simulations. They’re very versatile and they’re just cool.

What hobbies and interests do you have?

I like reading, travelling, and juggling.