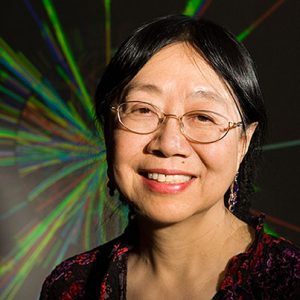

Congrats to UW–Madison physics Prof. Sau Lan Wu, who announced her retirement effective January 1, 2026. One of the first two women on the physics faculty when she joined as an assistant professor in 1977, her nearly 50-year career stands as one of the most consequential in modern experimental particle physics.

“Sau Lan is truly remarkable and irreplaceable,” says UW–Madison experimental particle physicist and department chair Kevin Black. “If I accomplish even one-third of what she has in her career, I will consider myself incredibly successful.”

Rising from humble beginnings in Hong Kong to becoming a central figure in high energy physics, Wu’s path began at Vassar College, where she graduated summa cum laude in 1963. She then earned her MA and PhD from Harvard, part of the first cohort of women ever awarded graduate degrees directly from the university. After a postdoctoral fellowship and research appointment at MIT, she joined UW–Madison as an assistant professor in 1977, was promoted to associate professor in 1980, and to full professor in 1983. She earned the UW–Madison titles of Enrico Fermi Professor, Hilldale Professor, and Vilas Professor.

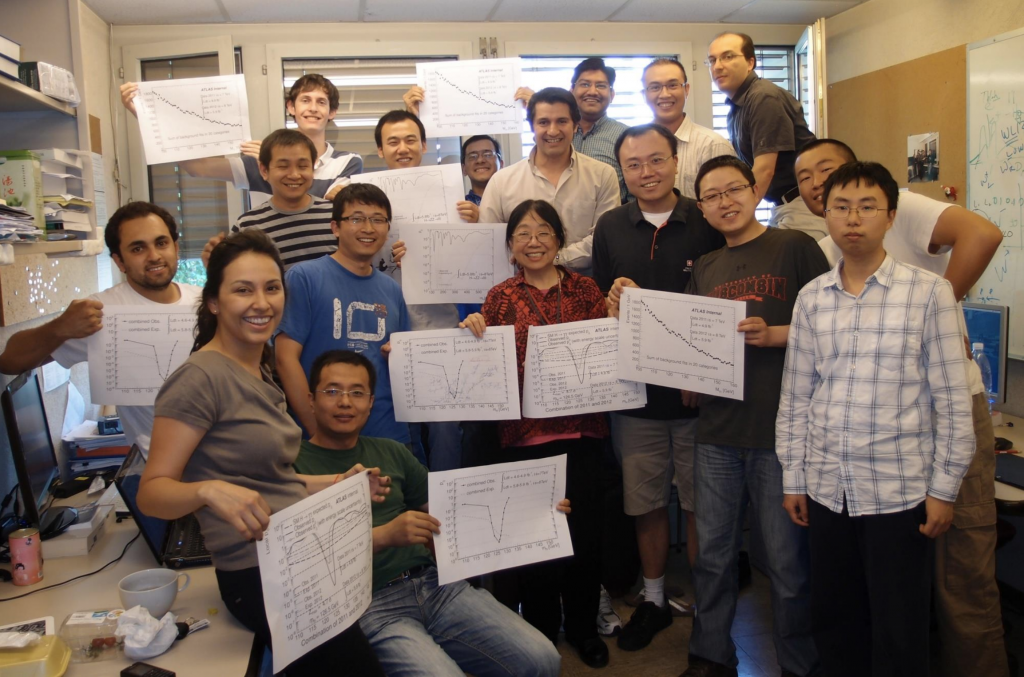

From her earliest days in the field, Wu gravitated toward the biggest scientific frontiers. She played key roles in three landmark particle discoveries: the charm quark in 1974 as part of Samuel Ting’s MIT/Brookhaven team; the gluon in 1979 through her pioneering work identifying three-jet events at DESY; and the Higgs boson in 2012, where her ATLAS group helped lead analyses of the H→γγ and H→ZZ*→4ℓ decay channels. Each discovery reshaped the Standard Model, and collectively they earned her a reputation as one of particle physics’ most influential experimentalists.

Wu is a Fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, a recipient of the European Physical Society Prize, and shared the 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics with the LHC collaboration. In 2022, the International Astronomical Union named a minor planet, Saulanwu, in her honor.

Through all these achievements, Wu remained devoted to guiding the next generation of experimental physics. 65 doctoral students completed their PhDs in her group, on major experiments from PETRA to LEP, BaBar, and the LHC. Of her former students and postdocs, 40 now hold faculty positions worldwide, and 18 are permanent staff scientists at major laboratories. Many others have gone on to high-impact roles in national science policy and the technology sector.

Says Steve Ritz, distinguished professor of physics at the University of California Santa Cruz and the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics and a former student with Wu:

“Sau Lan pointed the way toward the most interesting questions, and she made sure we had what we needed for success. We always knew that we could try new approaches to problems and that she had our backs if we hit a bump in the road. She also made sure we didn’t just bury ourselves in our own work: there seemed to be a constant flow of great physicists visiting the group, and Sau Lan introduced us to each one. We were encouraged to attend their seminars and we were invited to lunch and dinner discussions. I now understand that Sau Lan was helping us develop our own sense of belonging in the field, while also pushing us to reach our full potential.”

John Conway, distinguished professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at UC Davis and former postdoc in Wu’s group, adds:

“I worked with Sau Lan as a postdoc on the ALEPH experiment at CERN for over five years. It was a fantastic time — her group was super lively and carrying out a lot of different work on the experiment, and which was then brand new. Sau Lan instilled in me the hunger for discovery that I have carried through the rest of my career, and demonstrated what it meant to be truly dedicated to this work. She was an inspiring leader and had genuine concern for the lives and careers of everyone who worked for her. I’ve tried to pay that forward in my own career.”

Even in the later stages of her career, Wu remained at the forefront of innovation. She championed the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into experimental physics, leading ATLAS’s first event-level anomaly detection study and advancing GNN-based tracking, GAN-based simulation, and early quantum machine learning applications for high energy physics. These efforts have helped prepare the field for the data-intensive future of the HighLuminosity‑ LHC beginning later this decade.

Wu has been featured on the front page of The New York Times, profiled in Quanta and Wired, invited to write for Scientific American, and highlighted in seven books celebrating scientific trailblazers and women in STEM, many aimed at sharing the excitement of discovery with children. The UW–Madison alumni magazine, On Wisconsin, featured her in a lengthy profile in 2019. She has delivered Vassar’s 150th Commencement Address, appeared on the cover of the AIP History Newsletter, and continued to be a sought-after speaker, including keynotes at SLAC in 2024 commemorating the 50th anniversary of the J/ψ discovery.

“Sau Lan is a legend in the field of experimental particle physics,” says Sridhara Dasu, an experimental particle physics professor at UW–Madison. “Her experiences will be inspiring for generations to come.”